Occupational health adviser Clare Tregoning looks at the benefits of undertaking a health-needs assessment.

A health needs assessment provides the opportunity to gain an awareness of the current health of the workforce and to identify the gaps in healthcare provision, as well as to make recommendations to the organisation (Phillips, 2013). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) defines a health-needs assessment as “a systematic method for reviewing the health issues facing a population, leading to agreed priorities that will improve health and reduce inequalities” (2005).

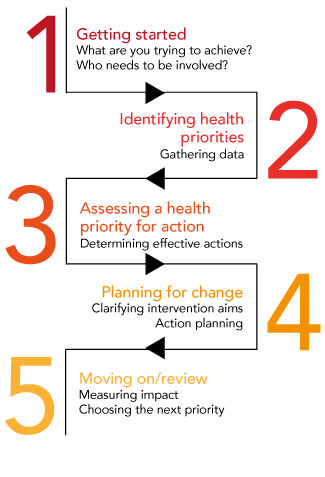

Phillips says that it is necessary to consider the health and safety aspects of the work being done, particularly regarding the risk assessment that is required to be carried out in all workplaces (Health and Safety Executive (HSE), 2000). The NICE guidelines on health-needs assessments provide a five-step linear approach, which is not unlike the HSE’s five steps to risk assessment.

This article looks at how one occupational health (OH) department identified and reviewed the current health needs of theatre scrub nurses at a local hospital, following a risk assessment by the theatre manager. A scrub nurse works within the sterile field of a surgical procedure alongside a surgeon, passing the equipment and instruments as required. The result of the risk assessment recommended interventions that were necessary to improve the health and wellbeing of operating theatre staff and provided guidance on how to implement them, as advised by Black (2012).

Impetus for the health-needs assessment

The theatre manager was concerned about the health and wellbeing of her staff as, during a four-month period, four scrub nurses had submitted incident reports indicating that they were suffering from back pain after undertaking routine work.

The team that experienced this problem works solely in the plastic surgery theatre and consists of four men aged between 25 and 49 and four women aged between 23 and 53. The manager noted that only 50% of these people had attended the mandatory manual handling training sessions instead of the required 100%. She raised her concerns with the OH department, and added that the theatre staff were largely unaware of the role of OH and the services it offers to employees.

The OH service explained that it: focused on employee healthcare needs, specifically those related to the work environment; supported managers in identifying risks to health and safety; and advised on measures to reduce risk and promote health, particularly those outlined in the HSE’s guidance tools for managing health and safety at work.

Identifying hazards

Hazards identified in the plastic surgery theatre included: manual handling; standing for long periods in a stressful environment; ergonomically unsuitable equipment; working with electricity and fluids; inhalation of smoke and fumes; slippery floors; chemicals, which are used to cleanse the skin; risk of inoculation injury through exposure to blood, body fluid and blood splashes; and sharp instruments, blades and needles.

People who work in operating theatres are at risk of sustaining an inoculation exposure. This is a term used to encompass needlestick injuries, sharps injuries and blood or body fluid splashes. The injuries are subdivided into two categories: those resulting from percutaneous exposure, such as needlestick and sharps injuries, where a blood- or body-fluid-contaminated object pierces the skin; and those resulting from mucocutaneous exposure, such as blood or body fluid splashes to an open wound, eye or mouth mucous membrane (Health Protection Agency (HPA), 2011).

All healthcare workers are at risk of sustaining a needlestiand it remains one of the most frequently reported injuries to healthcare employees (HPA, 2011). Considering all factors that affect infection transmission following a needlestick injury, it is imperative that all inoculation exposures are reported to OH so that appropriate treatment, follow-up care, advice and counselling can be provided (HSE, 2013). To provide protection against the hepatitis B virus, all healthcare employees including theatre personnel are offered hepatitis B vaccinations, in line with HPA guidelines (2011).

Safety equipment

Personal protective equipment is provided for theatre personnel and includes waterproof sterile scrub clothing, hats, gloves, masks and eye shields. The operating table can be adjusted for height and position. The electric diathermy and cutting diathermy equipment are earthed through the diathermy machine, and an air conditioning/smoke evacuation system is in place. Blood and fluid spillages are minimised with the aid of suction canisters, which collect excess spillage of fluids.

The theatre personnel raised an issue regarding the static-height instrument trolley and had reported back pain following the use of this equipment. A risk assessment also highlighted a need for height-adjustable instrument trolleys to ergonomically accommodate the different heights of the people using the equipment (Tompa et al, 2010). A height-adjustable trolley would reduce bending and stretching by allowing adjustment for each person’s individual needs according to their height and build (Fabrizio, 2009).

It was noted that the four people reporting back pain had failed to attend the yearly update for manual handling training and had not performed the recommended dynamic risk assessment before using the static-height trolley, thus reinforcing the importance of manual handling training and dynamic risk assessment (HSE, 1992). Dynamic risk assessment is the continuous process of assessing individual actions to identify, assess and eliminate risk. Following the submission of the incident reports, the four people suffering from back pain were referred to OH for assessment and advice.

OH services offered to staff

Although a review of sickness absence statistics for theatre personnel over the past 12 months found a 0% sickness absence rate, there is potential for absence caused by a musculoskeletal condition if pain is not addressed. Once employees have reported an incident relating to a musculoskeletal injury they should be referred to OH by management. Within the hospital setting, however, any employee may self-refer to OH, where they are able to access early intervention and treatment as appropriate (Shaw et al, 2011; Black, 2008).

Hospital employees are able to access health and wellbeing advice, early assessment and health interventions through the OH service. There is also early access to physiotherapy, health advice and stress counselling (Waddell and Burton, 2006).

A “health and wellbeing service” had been implemented by the OH department, with the aim of promoting health for all employees and as a tool for supporting a healthy workforce. It is open to all health board employees and is promoted through the health board intranet site, leaflets, posters, seminars for managers and employees, and from within the OH department. The aim of this service, through its dedicated intranet page, is to provide easily accessible information, a resource for self-help and signposting for health promotion and other initiatives.

Information on health topics such as alcohol, smoking, substance misuse, exercise and healthy eating are provided, together with links to a variety of healthy living campaigns and websites including the British Heart Foundation, BBC Health and Stop Smoking Wales.

The counselling service and information about a stress management workshop are outlined on the site, together with a detailed overview of what this confidential service offers to health board employees. A self-help book list can be accessed, along with self-help factsheets on stress and mental health. As part of the health wellbeing initiative, the external service of a complementary therapist is also offered to all health board staff, who provides aromatherapy, Reiki and reflexology.

The “muscle and joint” service offered by OH provides advice on the management of back pain. Once accessed, this service can provide advice over the telephone or, if more management is required, can refer people directly to physiotherapy for further assessment and treatment. Historically, employees accessed services such as physiotherapy through their GP or the OH department, with varying waiting times – delays in treatment were found to lengthen sickness absence and prolong a return to work (Waddell and Burton, 2006). However, with a system of direct referral, assessment and treatment, waiting times are cut, people are treated earlier and sickness absence and return-to-work times have been decreased.

Back pain and stress are reported to be two of the main contributors to long-term sickness absence among employees (CIPD, 2013) and the health and wellbeing service will be under review to establish whether or not it has been effective in improving sickness absence levels across the health board.

Conclusion

The health-needs assessment showed that no health surveillance was necessary for theatre staff. However, it did identify that equipment modifications were required to minimise the risks of musculoskeletal injuries (Schulte et al, 2012) and to reduce the worker-reported back pain. The standard-height instrument trolley was found to be inappropriate, and the assessment established that this equipment requires modification or replacement to become height adjustable to accommodate the ergonomic requirements of the people using it.

The assessment also found that it would be appropriate to raise awareness of the role of OH and the services it offers to promote health and to reduce the risk of musculoskeletal conditions and injuries at work. This can be achieved by the OH service raising its profile with all employees, offering support for those suffering from stressful conditions and providing access to the health and wellbeing service through information leaflets and encouraging the use of the hospital intranet.

Although the sickness absence rate stood at 0% in theatres over the past 12 months, the assessment highlighted that early intervention in treating musculoskeletal disorders is likely to reduce any future long-term sickness absence and improve return-to-work timescales (Schultz et al, 2008).

Following the health-needs assessment, the OH service made the following recommendations:

- An up-to-date risk assessment should be undertaken by the theatre manager, particularly with regard to equipment used. Any necessary modifications should be carried out immediately.

- All employees should attend the mandatory manual handling training and subsequent yearly updates and a departmental record should be kept of attendance at such training, with a recall system so that attendance will rise from 50% to 100%.

- All employees who have sustained an injury at work should be referred to OH within 24 hours of the reported injury, and all musculoskeletal conditions should be advised of the health and wellbeing service in order to access early assessment and treatment.

- All health board employees should have an increased awareness of the role of OH and the services it offers.

- An evaluation should be undertaken in five months to monitor the effectiveness of the equipment modifications and advised interventions.

References

Black C (2008). “Review of the health of Britain’s working age population: Working for a healthier tomorrow”. London: The Stationery Office.

Black C (2012). “Why healthcare organisations must look after their staff”. Nursing Management; vol.19, issue 6, pp.27-30.

CIPD (2013). Absence management 2013: Annual survey report.

Fabrizo P (2009). “Ergonomic intervention in the treatment of a patient with upper extremity and neck pain”. Physical Therapy; vol.8, issue 4, pp.351-360.

Health and Safety Executive (2014). Management of health and safety at work.

Health and Safety Executive (2011). Manual handling at work: A brief guide.

Health and Safety Executive (2013). Health and Safety (sharps instruments in healthcare) Regulations 2013: Guidance for employers and employees.

Health Protection Agency (2011). “Eye of the needle: UK surveillance of significant occupational exposure to bloodborne viruses in healthcare workers”. London: HPA.

Koneczny S (2009). “The operating room: architectural conditions and potential hazards”. Work; vol.33, issue 2, pp.145-164.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2005). Health needs assessment: a practical guide.

Phillips A (2013). “Management of OH services”. In: Thornbory G (ed). Contemporary Occupational Health Nursing: A Guide for Practitioners. Oxon: Routledge.

Shaw W, Main C, Johnson V (2011). “Addressing occupational health factors in the management of low back pain: implications for physical therapist practice”. Physical Therapy; vol.91, issue 5, pp.777-789.

Shultz IZ, Crook J, Berkowitz J, Milner R, Meloche GR, Lewis ML (2008). “A prospective study of the effectiveness of early intervention with high-risk back-injured workers: a pilot study”. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation; vol.18, issue 2, pp.140-151.

Tompa E, Dolinschi R, Oliveira C, Amick B, Irvin E (2010). “A systematic review of workplace ergonomic interventions with economic analyses”. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation; vol.20, issue 1, pp.220-234.

Sign up to our weekly round-up of HR news and guidance

Receive the Personnel Today Direct e-newsletter every Wednesday

Waddell G, Burton K (2006). “Is work good for your health and well-being?”. London: The Stationery Office.

Clare Tregoning is occupational health advisor at Morriston Hospital, Swansea.