Priscilla Wong, head of occupational health at the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) examines how occupational health policies and interventions for prison staff were delivered – or rethought – during the pandemic. This included considering the careful balance between employee need and public sector value for money.

The UK’s prison service is a complex, high-risk environment and its occupational health policy aims to deliver holistic workplace health and wellbeing interventions for prison workers.

The maintenance of prison staff health can be considered a public issue. If staff have suboptimal health, they will not be effective in delivering the prison service’s vision, namely: “Working together to protect the public and help people to live law-abiding and positive lives”.

These are unequivocally big issues for the government, but were especially so in a pandemic-triggered VUCA world (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous), while crime is already an intractable problem in society (Head and Alford, 2015). At the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, the prison service was facing several complex issues:

- The Ministry of Justice (MOJ) highlighted a workforce capacity and capability concern (MOJ, 2021).

- The Institute for Government (2023) highlight that the use of inexperienced prison staff can damage the quality of support and supervision within prisons (The Institute for Government, 2023).

- Prison officers face a high risk of burnout (Clements and Kinman, 2021).

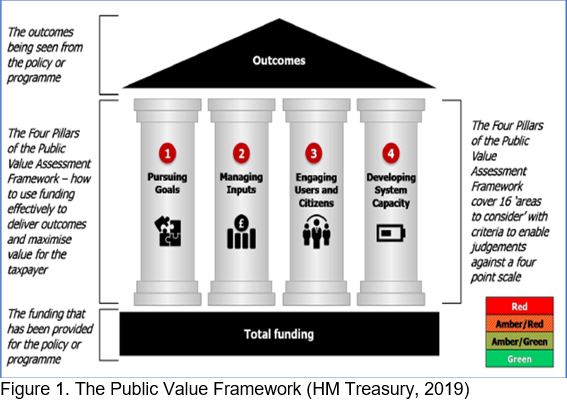

Value for money is a key consideration in any public sector project. For this reason those involved in policy decisions in public services should have regard to the ‘Public Value Framework’ (figure 1).

This was introduced by Michael Barber and examines how to embed continuous productivity measurement and improvement across the public sector. The framework is a practical tool for assessing the chances that public value is being maximised, and its pillars ultimately assess the process of turning funding into policy outcomes.

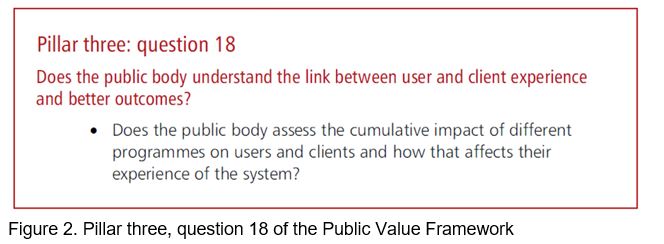

A priority in the public sector today is to deliver personalised outcomes rather than services. This led me to explore pillar three: question 18 of the framework, which considers the extent to which a public body is aware of how user experiences affect outcomes that add public value.

An example of how this was put into action was the implementation by His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) of an employee post-Covid syndrome service for both physical and mental health problems.

We wanted employees using this service to have a higher care-related quality of life and better psychological wellbeing. They would be less likely to require GP appointments and less likely to attend A&E, compared to those suffering long Covid and not having access to an NHS long Covid service.

Health and prisons

This employer-funded OH intervention could thereby alleviate pressure on other public health services, as well as help the prison service keep hold of valuable workers.

We found that the outcomes of this particular intervention were difficult to quantify, especially in monetary terms, at the early stages of implementation. However, employee narratives gave powerful explorations of how individuals interacted with the service and what it meant to them.

For example, one employee commented: “Long Covid has driven me to some pretty dark places since December last year. This programme is a sense of hope and knowledge that I’m not the only one going through this, it has felt really very lonely and isolating due to the limited understanding of long Covid but you have helped no end to show things can and should improve given time and process…”.

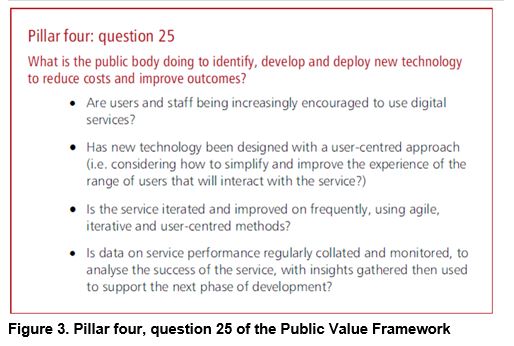

During lockdown, employees have had to engage with health and wellbeing in a different way, namely moving away from face-to-face consultations to completely remote services. Up to this point, there was widespread resistance to change OH consultations to a telemedicine-based model. Overnight, Covid-19 had expedited this change.

Once embedded, the remote service was found to be particularly beneficial for employees and managers alike, for example it was seen as more convenient due to removing the need to travel and shorter waiting times for appointments.

In addition, the remote delivery mode strengthened the third-party provider’s section of the delivery chain, as a wider pool of clinicians were more accessible than before. This project was assessed against pillar four, question 25 of the Public Value Framework, as shown in figure 3.

We tracked success via several key performance indicators and, despite increased demand in services, 100% appointments were offered within the 48-hour KPI period. The temporal perspective was that a long-term behavioural change is likely to have been created.

Unsuccessful outcomes

However, as many organisations have experienced, not every project is successful. The OH policy team were urgently commissioned to scope and deliver a training programme, Mental Health Impact on Workforce Policies aimed at policy makers within the organisation. We were under pressure to deliver at pace because, the intervention had already been reported as live in the public domain via the “Covid-19 mental health and wellbeing recovery action plan” (HM Government, 2021).

A third party and a psychologist within in our policy team worked rapidly to develop the course, pilot the initial programme and communicate the offer across the prison estate.

The single point of failure was that the key intended users did not engage with the training programme. Stakeholder feedback was that, with the pressure of the pandemic on workloads, they simply did not have time to undertake the training.

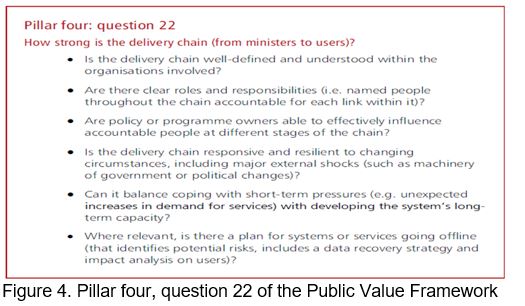

Pillar four ‘Barber’ states that the chain is only as strong as its weakest link, that if any of the links are broken, effective delivery of policy improvements will be virtually impossible.

Using the first three bullet points in the Public Value Framework pillar four, question 22, (as outlined below in figure 4) we reflected on the elements of the programme which disadvantaged progress and success.

- Is the delivery chain well-defined and understood within the organisations involved?

- Are there clear roles and responsibilities?

- Are policy or programme owners able to effectively influence accountable people at different stages of the chain?

As much as we wanted the training programme to succeed and meet the ambition of developing organisations and individuals, the following challenges emerged:

- Power determined the implementation of the policy intervention rather than a defined problem or a legitimate need.

- There was no evidence or plausible narrative to indicate that this was a problem requiring policy to address it.

- There was no effective accountability in place.

- Communication did not reach all stakeholders in a reasonable timeframe.

- There was no whole systems approach.

- The sense of urgency competed against our team’s other priorities.

- There was a lack of awareness of other teams’ capacity during the pandemic.

- To tackle the problem, I took the action which followed the evaluation steps as outlined by Cairney (2019).

- Assessing the extent to which the programme was successful.

- Checking if the programme was appropriate, implemented correctly, and had the desired effect.

- Considering if the programme should be continued, modified, or discontinued.

In this case, we considered discontinuing it but, instead, I took the decision to postpone roll-out of the training. In line with the approach of Cairney and St Denney (2020). I wanted to at least try to engage in the policy intervention long enough to exploit windows of opportunity.

On reflection, as soon as I suspected the programme would not be viable, a time-efficient approach would have been to articulate the barriers and setbacks and modify the project at much earlier stage before resources were committed.

Ultimately, it is important to consider perspectives and insight from a range of stakeholders to ensure that top-down policy and the real-world situations align.

References:

Cairney P (2019). ‘Understanding Public Policy: Theories and Issues’, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, London. Available at: ProQuest Ebook Central.

Cairney P and St Denny E (2020). ‘Why Isn’t Government Policy More Preventive?’, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clements A J and Kinman G (2021). ‘Job demands, organizational justice, and emotional exhaustion in prison officers’, Criminal Justice Studies, DOI: 10.1080/1478601X.2021.1999114

Head B W and Alford J (2015). ‘Wicked Problems: Implications for Public Policy and Management’, Administration & Society. 47(6) 711–739. DOI: 10.1177/0095399713481601

HM Government (2021). ‘Policy paper: COVID-19 mental health and wellbeing recovery action plan – Our plan to prevent, mitigate and respond to the mental health impacts of the pandemic during 2021 to 2022’. Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-mental-health-and-wellbeing-recovery-action-plan

HM Treasury (2019). ‘The Public Value Framework: with supplementary guidance’. Available at: Public Value Framework with supplementary guidance (publishing.service.gov.uk)

Institute for Government (2019). ‘Performance Tracker: Prisons’. Available at Prisons | The Institute for Government

Ministry of Justice (15 July 2021). ‘Corporate report: Ministry of Justice Outcome Delivery Plan: 2021-2022’. Available at Ministry of Justice Outcome Delivery Plan: 2021-22 – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Sign up to our weekly round-up of HR news and guidance

Receive the Personnel Today Direct e-newsletter every Wednesday