Stigma surrounding suicide means many people shy away from talking about it or questioning sudden changes in a person’s behaviour, but engagement from colleagues and occupational health is vital for suicide prevention. Dr Simon Walker explains how the ‘RED’ approach can potentially save a life.

Suicide remains one of the most common causes of death across the world. It is estimated to occur on average every 11 minutes in the USA (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020), and it has been identified as the fourth leading cause of death among 15-29-year-olds globally (World Health Organization, undated).

In England and Wales, rates of suicide had steadily declined from 1981 onwards. But since 2017 there have been shallow peaks in suicide rates, with current figures showing a steady rise.

These statistics demonstrate that suicide demands attention, but they do not present a clear enough understanding of the particulars of individual suicide actions, what impacts these, or the opportunity for prevention presented by work and occupational health.

The impact of suicide

Suicide prevention at work

Every year it is estimated that 700,000 to 800,000 people globally die by suicide, with potentially a further 20,000,000 attempts, based on the general estimate that for each death there are 25 attempts (Western Michigan University, undated). This is a significant number and is difficult to ratify due to the complexity of suicide reporting, identification, and societal response. However, if these estimates are to be accepted, this implies that 0.25% of the world population each year attempts suicide. To put that in context, Cancer Research UK (undated) estimates that there are 17 million new cases of cancer each year. Following the same equation, against a global population of 79.4 billion, new cases of cancer each year represent 0.21% of the worldwide population. These numbers are extremely basic in presentation, but they demonstrate the importance of suicide awareness and prevention.

What is clear is that every suicide is a tragedy that affects families, communities and entire countries, leaving long-lasting impacts on the people left behind. So much so that bereavement through suicide has been highlighted as a specific risk factor for suicide, with estimates of increased risk up to 65% (Pitman et at, 2016).

It should also be noted that suicide does not just occur in high-income countries but is a global phenomenon in all regions of the world. It is widely recognised that socioeconomic factors can play a pivotal role in suicidal action. The World Health Organization (2020) reported that over 77% of global suicides occurred in low- and middle-income countries in 2019.

Within England, people living in the most deprived areas have a higher risk of suicide than those living in the least deprived areas. The suicide rate in the most deprived 10% of areas (decile) in 2017-2019 was 14.1 per 100,000, which is almost double the rate of 7.4 in the least deprived decile, according to the Office for National Statistics (House of Commons Library, 2022).

The reasons why suicide is so stigmatised are often context-dependent and related to factors such as mental illness, relationship problems, finances, loss of housing, substance use, and job loss.”

Suicide is a serious public health problem; however, it is increasingly understood that suicides can be preventable with timely, evidence-based, and often low-cost interventions. One of the best places to engage with this preventative method is the workplace.

An uncomfortable issue

One of the key issues is the fear and stigma associated with suicide. An article in The Atlantic explained that: “Death is always messy and hard to understand, suicide even more so. It’s a broad (and increasing) public-health problem with a million different faces, affected by many factors.” (Beck, 2018).

This is absolutely true. Death within modern society typically represents finality, loss, and ending. Funerals tend to be very awkward events, often with high emotion and confusion, even anger. When suicide is brought into the equation, often accompanied by ignorance, stigma and anguish, the topic of death can become so much harder to discuss. Unfortunately, one of the best ways to prevent suicide is to discuss uncomfortable issues, such as death, emotion, and trauma.

The reasons why suicide is so stigmatised are often context-dependent and related to factors such as mental illness, relationship problems, finances, loss of housing, substance use, and job loss. As such, the trauma and losses of people’s lives and the ways they respond to them can be infinitely varied, meaning that there is no singular factor that can aid prevention.

There is no silver bullet to assuage suicide risks. However, there are areas of opportunity where support can be established; where co-workers and management often have a habitual relationship with each other and are able to detect changes in behaviour, mood, and speech which may be indicative of suicidal thoughts or behaviours.

Recognising suicide risk

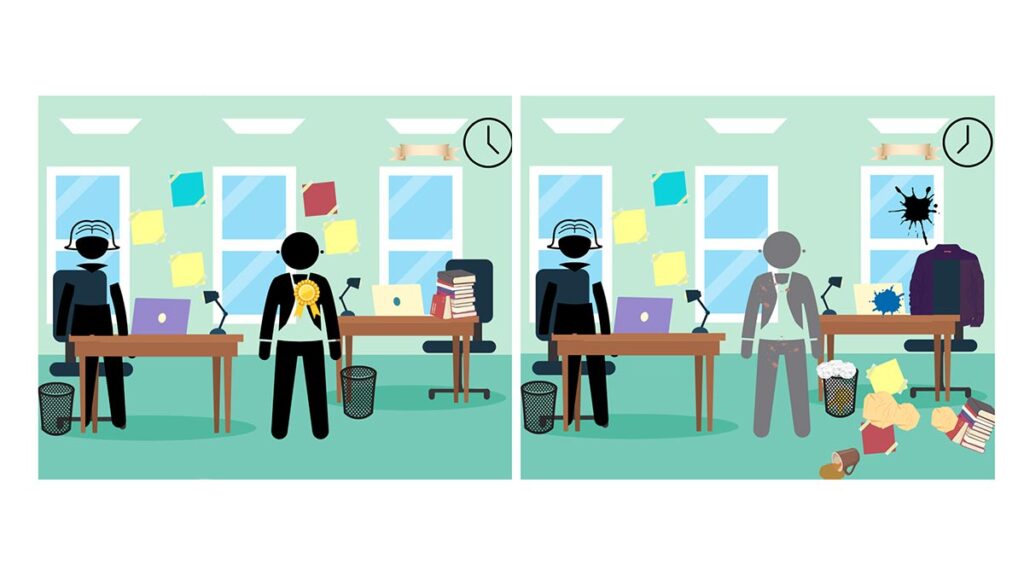

An easy way to visualise the methods of recognition for suicidal ideation, thoughts, or behaviour is through a basic narrative from the cartoons below. Jay and Jacque have worked together in the same office for many years.

Jacque had recently noted that Jay’s work practices and behaviours have changed. Jay previously was an award-winning employee, fastidious about having a tidy workspace, always meeting deadlines, and being engaged with the staff around them. Recently, Jacque has released that Jay is repeatedly late, has an untidy workspace, and is not doing well at work. Jacque is worried about approaching Jay but knows that they need to. However, they are not sure how.

There is no silver bullet to assuage suicide risks. However, there are areas of opportunity where support can be established; where co-workers and management often have a habitual relationship with each other and are able to detect changes in behaviour, mood, and speech.”

In this example Jacque is aware of the change in Jay due to their familiarity at work but is unsure of how and if to engage with them. This is a common issue, with individuals often feeling uneasy about approaching others about their behavioural change. There is also a question of responsibility, with some individuals feeling that it is not their place to get involved, whereas others may fear taking responsibility for someone else’s mental health. In all cases both Jay and Jacque need help, and the employer is uniquely suited to support them.

In the UK, the Health and Safety Executive provides extensive guidance on how to support individuals with mental health assistance and suicide prevention methods. The HSE guidelines on suicide prevention say that “work-related factors may contribute to feelings of humiliation or isolation. An issue or combination of issues such as job insecurity, discrimination, work stressors and bullying may play their part in people becoming suicidal.” (Health and Safety Executive, undated). In all of these cases, the HSE emphasises that it is the responsibility of the employer to support the individual by reducing job stress, such as providing options for flexibility, guidance to counselling and medical services, time off for engagement with legal services, as well as refer to occupational health. In the case of Jay and Jacque, the guidance from the HSE is clear:

If you think someone may be suicidal, encourage them to seek help from their GP, employee assistance programme (EAP) or a charity such as the Samaritans, or to talk to a trusted friend or family member. Signs that someone is struggling include:

- ups and downs in their mood

- not wanting to mix socially any more

- changes to their routine, like sleeping or eating

- seeming flat or low on energy

- neglecting themselves, showering less, or caring less about their personal appearance

- making reckless or rash decisions

- increased alcohol or drug abuse

- being more angry or irritable than usual

- talking about suicide or wanting to die in a vague or joking way

- giving away their possessions

- saying goodbye to people as if they won’t see them again.

The ‘RED’ approach

Ultimately, the key aspects for suicide prevention at work are: Recognition, Engagement, and Direction, or the ‘RED’ approach.

Recognition is an important and often difficult step. However, when combined with some form of engagement this can be potentially life-saving, simply by helping an individual to recognise their own intentions or feelings.

When discussing suicide there needs to be safeguards to protect all individuals involved. Self-care is especially important, as support for the suicidal individual can have a negative impact on the individual who intervenes.”

Engagement can be difficult as well, due to issues such as the fears raised by Jacque, who was concerned about talking responsibility or overstepping their bounds. Part of this is often related to the embarrassment and stigma of suicide. In other cases, there can be a lot of fear, especially in the case of potentially causing suicidal action through discussion. Research by Dazzi et al (2014) confirmed that talking about suicide has no statistical link to any subsequent act. Their research echoed the standard advice now followed by the NHS and mental health charities, that talking about suicide and potential suicidal behaviour typically plays a positive role in suicide prevention.

When discussing suicide there needs to be safeguards to protect all individuals involved. Self-care is especially important, as support for the suicidal individual can have a negative impact on the individual who intervenes. Therefore, it is beneficial for the supporting party to have knowledge of best practice and support techniques provided by their employer, complete with a range of services they can signpost the suicidal individual towards. This resource from Mind illustrates ways in which people who have considered suicide found help and support through discussion. There are also helpful resources available on YouTube.

In all cases of discussing suicide, suicidal intent or mental health, it is important to approach the subject with care and kindness. Using open and closed questions are useful to establish intent and encourage individuals to talk. However, in most cases, it is best to support the individual by directing them to the appropriate support services. All employees should have access to the guidance mentioned in this article.

Suicide is preventable. Some suicide cases are planned down to the minute detail, whereas others are a sudden decision taken often in the midst of significant emotional distress. In any case, suicide can be prevented through the practice of Recognition, Engagement, and Direction (RED). The role of the workplace can be instrumental in this process, as it can provide an environment to identify, support, and orientate individuals in need towards services to assist them.

Still, the health and safety of one individual should not compromise the health of another, even with the best of intentions. Therefore stringent policies and support mechanisms, as identified by the HSE, must be made available within the workplace, with clear communication on their accessibility and usage.

References

Beck, J (2018). ‘When Will People Get Better at Talking About Suicide?’The Atlantic, Available from: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2018/06/when-will-people-get-better-at-talking-about-suicide/562466

Cancer Research UK (undated) Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/worldwide-cancer

CDC (2020) Underlying cause of death, 1999–2019. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/Deaths-by-Underlying-Cause.html

Dazzi T, Gribble R, Wessely S, Fear, NT (2014). Does asking about suicide and related behaviours induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychol Med. 2014 Dec;44(16):3361-3. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001299. Epub 2014 Jul 7. PMID: 24998511.

Health and Safety Executive (undated) Suicide Prevention. Available from: https://www.hse.gov.uk/stress/suicide.htm

House of Commons (2022) Suicide Statistics. Parliament: House of Commons Library. Available from: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7749/

Pitman AL, Osborn DPJ, Rantell K, et al (2016) Bereavement by suicide as a risk factor for suicide attempt: a cross-sectional national UK-wide study of 3432 young bereaved adults BMJ Open 2016;6:e009948. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009948

Western Michigan University (undated). Available from: https://wmich.edu/suicideprevention/basics/facts

Sign up to our weekly round-up of HR news and guidance

Receive the Personnel Today Direct e-newsletter every Wednesday

World Health Organization (undated) Suicide Prevention. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

World Health Organisation (2020) Suicide – Key facts. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide