Burnout in healthcare not only poses a major threat to health but can also threaten job performance. Properly managing burnout needs an organisational-wide and individual response. Occupational health professionals also have a pivotal role to play, writes Professor Gail Kinman.

Working in healthcare can be satisfying, but employees are at a high risk of burnout, with wide-ranging consequences for their health and performance.

Effective interventions are needed to prevent and manage burnout. This article draws on a guide recently published by the Society of Occupational Medicine focusing on the meaning of burnout, the signs and symptoms, and the implications for healthcare employees, organisations and patients/clients.

Some interventions to reduce the risk of burnout are outlined, with particular focus on primary and tertiary strategies. The key role played by occupational health professionals in helping organisations manage its negative effects is considered. Although the article focuses on healthcare, there are key messages for other sectors.

What is burnout?

Burnout is a syndrome resulting from chronic, unmanaged workplace stress (WHO, 2019). It can manifest itself in many ways, but common signs include:

- Emotional changes. These can include anger and frustration; anxiety and panic; feeling overwhelmed and helpless; loss of enthusiasm and a sense of meaningless; loss of enjoyment of work and sense of doing a good job.

- Cognitive changes. These can include lack of concentration; procrastination; cynicism and suspicion of others; rumination over minor issues; doubts about competence.

- Physical changes. These can include insomnia and chronic fatigue; medically unexplained symptoms; increased vulnerability to infections.

- Social changes. These can include feeling alienated from other people and alone in the world.

- Behavioural changes. This can include feelings of irritability, lacking empathy; self-medication with food, substances or alcohol; neglecting personal needs; distancing oneself from others and from work.

Longitudinal studies indicate burnout is a developmental process characterised by three stages (Taris et al, 2007).

Burnout in healthcare

Put OH at heart of tackling NHS burnout, urges SOM

Thus, an emotionally demanding job can deplete an employee’s emotional resources, leading to emotional exhaustion. As self-protection, the employee may then become more cynical, depersonalise others and reduce their engagement in work.

In turn, such feelings and actions can engender feelings of professional inefficacy and lack of fulfilment. These negative self-evaluations intensify emotional exhaustion reinforcing the burnout experience over time.

Although not a medical condition, people who are burned out are vulnerable to diagnosable mental health conditions, including depression, generalised anxiety disorder or substance misuse (van Dam, 2021). Awareness of the signs and symptoms of burnout is therefore crucial to enable early interventions.

Risk factors for burnout

According to the 2022 NHS workforce survey, 34% of the 636,348 participants reported feeling burned out by their work and 37% found it emotionally exhausting (NHS, 2022).

To reduce this risk, insight into the occupational, organisational and individual risk factors that increase people’s vulnerability to burnout is needed. In terms of job role, general practitioners, critical care nurses, and frontline ambulance staff appear to be particularly vulnerable (Kinman and Teoh, 2018; Kinman et al, 2020).

Moreover, findings that many trainee and newly qualified healthcare professionals are showing signs of burnout so early in their career gives cause for concern (GMC, 2022).

A particularly powerful risk factor for burnout among healthcare professionals is working in a culture requiring sustained compassion from employees while overlooking (or even stigmatising) help-seeking (Muir et al, 2022).

Other organisational-level hazards include: high demands, long hours, short-staffing, lack of social support, excessive and poorly managed change, and poor leadership and management (Kinman and Teoh, 2018; Kinman et al, 2020).

Recent research has identified moral injury as a major risk factor for burnout; this describes the distress resulting from actions (or inactions) violating an employee’s moral or ethical code.

More CPD

CPD: Burnout – risk factors and solutions (webinar)

CPD: Tackling stress in construction

CPD: Why OH professionals require an understanding of occupational hygiene

Moral injuries were observed more frequently during the Covid-19 pandemic in response to the compromised care and difficult decisions or actions that many healthcare professionals were obliged to take (Denham et al, 2023).

As well as organisational risk factors, some individual characteristics have been found to increase vulnerability to burnout, for example, dysfunctional perfectionism, a ‘rescuing orientation’ to helping others, and over-involvement with patients/clients (Blanch et al, 2018; Kinman and Grant, 2021).

Another risk is ‘affective rumination’, where people struggle to switch off psychologically from work-related concerns (Jackson-Koku and Grime, 2019) with serious implications for their recovery and health, as well as work-life balance.

There is growing evidence that people who are neurodiverse may be at greater risk of burnout (Raymaker et al, 2020). This can be more challenging to detect in neurodiverse employees, as it can manifest itself in different ways, with signs including chronic exhaustion, reduced tolerance to sensory stimuli, and increased challenges with memory and communication skills (Tomczak and Kulikowski, 2023).

While identifying signs of burnout at an early stage in order to tailor appropriate interventions, it should be recognised that neurodivergent employees can find it difficult to withdraw from stressful situations and seek help.

The wider impact of burnout

Burnout in healthcare has wider implications. The sector is experiencing major recruitment and retention challenges and burnout is a common reason for leaving (Hodkinson et al, 2022).

It also poses risks for job performance: employees experiencing burnout can struggle to engage with others in an empathic and compassionate way, thus impairing the quality of interactions with patients/clients (Pavlova et al, 2022).

Moreover, a recent review found that doctors who experienced burnout were twice as likely to be involved in a patient safety incident (Hodkinson et al, 2022). It should be emphasised, however, that healthcare professionals who are experiencing burnout typically make considerable efforts to ensure that patients do not suffer, often at great personal cost (Montgomery et al, 2019).

Managing burnout

Although burnout is recognised as a response to unmanaged work-related stress, interventions are considerably more likely to target the individual than the organisation.

While healthcare professionals undoubtedly need effective coping skills, even the most resilient will struggle to remain healthy and productive in an environment that fails to support their wellbeing.

It is essential for organisations to prevent burnout by identifying and modifying the risk factors and promoting good quality work, as well as supporting employees experiencing difficulties.

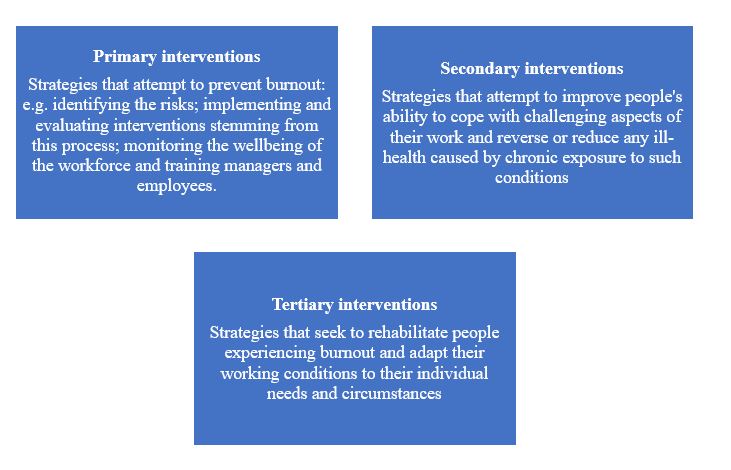

A multi-level, systemic approach is recommended with strategies at primary (organisational), secondary (individual) and tertiary (rehabilitation) levels.

Some examples of interventions at each level are provided below, with particular focus placed on organisational strategies.

Primary-level interventions

Assessing risk

A process has been developed to help organisations ensure that conditions are in place to reduce the risk of burnout and help employees remain healthy (Leiter and Maslach, 2005). It is particularly relevant to socially connected, values-based organisations such as healthcare. The six areas for attention are:

- Monitoring workloads to ensure they are manageable.

- Providing opportunities for professional autonomy and influence decision-making.

- Recognising good work, offering intangible rewards (feeling appreciated) as well as tangible rewards (such as pay and job security).

- Ensuring people feel they belong and that the work community is supportive.

- Fair and respectful treatment.

- Ensuring that people feel that the work they do is meaningful and congruent with their personal values.

Training leaders and line managers

Leaders and line managers are key to reducing burnout and enhancing wellbeing. There is evidence that workers in organisations led by people who are compassionate, inclusive and ethical are more healthy, engaged and motivated (West, 2021).

A compassionate leader focuses on relationships, empathises with their distress and takes thoughtful, intelligent action to support them. Line managers are particularly well placed to identify the early signs of burnout and often the first point of contact when employees are struggling to cope. Line managers therefore need appropriate training and sufficient time to support the wellbeing of themselves and their employees.

Taking a person-centred approach

As people respond differently to burnout, a person-centred approach will be beneficial. Wellness actions plans (WAPs) are designed to help managers support employees’ mental health and can be adapted to identify signs of burnout.

Formulated by the charity Mind, WAPs are personalised, practical tools that can identify what keeps people well at work, what threatens their wellbeing and the type of support they need if they are struggling.

WAPS are particularly useful when people return to work after experiencing health difficulties such as burnout, as they can facilitate structured conversations about their support needs and the adjustments that might be required.

Reducing the risk of moral injury

As discussed above, moral injury has become a common source of burnout for healthcare professionals. It is crucial to prepare employees at an early stage for the moral challenges of healthcare work and raise awareness of the risks of moral injury.

This can be accomplished by ensuring that people are aware that, despite their best efforts, undesirable outcomes (for example, mistakes and deaths) may occur and encouraging discussions between colleagues about potentially morally injurious events and the impact on them.

Developing self-regulation skills to disrupt negative patterns of thinking and behaviour can also restore balance when ethical challenges occur (Rosen et al, 2022; Williamson et al, 2021).

Individual-level interventions

Although organisational-level interventions are essential in order to protect against burnout, practitioners are also responsible for developing the skills and resources to help them manage what can be a highly pressured working environment.

Some effective interventions include self-reflection to help identify individual reactions to stress and the type of events people find most challenging, and psychoeducation to gain insight into the psychology of burnout and its management.

Emotional writing or journaling can also be protective by helping people process emotional reactions to work events, whereas mindfulness can aid self-compassion and help people prioritise self-care.

A strong network of supportive people also offers protection against burnout, with nurturing professional relationships from colleagues/peer groups being particularly important.

Setting clear boundaries between work and personal life, disengaging oneself mentally from work, and implementing appropriate compensatory strategies can also reduce early symptoms of burnout and the risk of more severe reactions over time.

Tertiary-level interventions

Tertiary interventions focus on the treatment of individuals who are experiencing burnout and how they might be supported following sick leave.

Occupational health professionals have a key role in managing burnout. They can inform strategy and best practice in its prevention and management at organisational and individual levels.”

Supporting employees to return to work (RTW) after burnout can be challenging, but some key steps have been identified. These include: monitoring employee wellbeing over time; initiating and planning their return; providing tools to support recovery; monitoring progress of the RTW process; supporting re-engagement with work; and monitoring the employee’s ability to cope with work (Karkkainen et al, 2019).

A personalised approach is needed to support a successful RTW, that involves ensuring a common understanding of the signs and symptoms of burnout and the unpredictability of recovery, as well as insight into its work-related causes, psychosocial risk factors, and any personal characteristics that might increase the risk of relapse.

Role for occupational health

Occupational health (OH) professionals have a key role in managing burnout. They can inform strategy and best practice in its prevention and management at organisational and individual levels.

OH can also have input at various stages. This can be from identifying the specific risk factors for burnout among healthcare professionals and raising awareness of the early warning signs through to developing RTW frameworks and negotiating phased approaches with line managers.

OH professionals also play a pivotal role in differentiating burnout from medical conditions, such as depression and trauma, as these will require alternative treatment.

It is crucial to recognise that burnout is a process so, when supporting employees, taking a detailed history of the progression to their current symptoms is needed as well as ensuring that mechanisms are in place to take timely remedial action.

As highlighted above, for burnout to be managed effectively any individually focused intervention should be alongside (but not instead of) appropriate organisational initiatives.

The ‘IGLOO’ model (comprising individual, group, leader, organisation, and overarching context) can guide this approach (Nielsen, 2022). It provides a holistic framework to identify challenges, issues and possible intervention activities that can be implemented at each level to manage burnout risks and support a sustainable return to work.

Organisations cannot afford to overlook burnout. It not only poses a major threat to health but can also threaten job performance.

Burnout is also a common reason for turnover, which is a serious concern in light of the staffing crisis in healthcare. Burnout is all too often seen as an individual ‘illness’, a failure to cope, or even a sign of weakness, which overlooks its true causes.

While individual-focused solutions are undoubtedly important, they will not be effective unless organisational interventions are also embedded in policy and practice. More information on the causes, signs and symptoms and management of burnout can be found in this SOM guide.

References:

Blanch, J M, Ochoa P, and Caballero, M F (2018). ‘Over engagement, protective or risk factor of Burnout?’ Sustainable Management Practices. London: IntechOpen, https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/64504

General Medical Council (2022). National Training Survey 2022, https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/how-we-quality-assure-medical-education-and-training/evidence-data-and-intelligence/national-training-surveys/national-training-surveys—doctors-in-training

Denham F, Varese F, Hurley M, and Allsopp, K (2023). ‘Exploring experiences of moral injury and distress among health care workers during the Covid-19 pandemic’. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12471

Hodkinson, A, Zhou, A, Johnson, J, et al (2022). ‘Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: systematic review and meta-analysis’. BMJ. Sep 14;378, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-070442

Jackson-Koku G and Grime P (2019). ‘Emotion regulation and burnout in doctors: a systematic review’. Occupational Medicine, 69(1), pp. 9-21, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqz004

Kärkkäinen R, Saaranen T, and Räsänen K (2019). ‘Occupational health care return-to-work practices for workers with job burnout’. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 26(3), pp.194-204, https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2018.1441322

Kinman G and Grant L (2022). ‘Being “good enough”: Perfectionism and well-being in social workers’. The British Journal of Social Work, 20;52(7), pp. 4171-4188, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcac010

Kinman G and Teoh K (2018). ‘What Could Make a Difference to the Mental Health of UK Doctors? A Review of the Research Evidence’. Society of Occupational Medicine and the Louise Tebboth Foundation, https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsopm.2018.1.40.15

Kinman G, Teoh K, and Harriss A (2020). ‘The Mental Health and Wellbeing of Nurses and Midwives in the United Kingdom’. Society of Occupational Medicine and the Royal College of Nursing Foundation, https://www.som.org.uk/sites/som.org.uk/files/The_Mental_Health_and_Wellbeing_of_Nurses_and_Midwives_in_the_United_Kingdom.pdf

Kinman G, Dovey A, and Teoh K (2023). ‘Burnout in Healthcare: Risk Factors and Solutions’. Society of Occupational Medicine, https://www.som.org.uk/sites/som.org.uk/files/Burnout_in_healthcare_risk_factors_and_solutions_July2023.pdf

Leiter M P, and Maslach C (2005). ‘Banishing Burnout: Six Strategies for Improving your Relationship with Work’. John Wiley & Sons, https://www.wiley.com/en-gb/Banishing+Burnout:+Six+Strategies+for+Improving+Your+Relationship+with+Work-p-9780470448779

Montgomery A, Panagopoulou E, Esmail A et al (2019). ‘Burnout in healthcare: the case for organisational change’. BMJ 30;366, doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4774

Muir K J, Wanchek T N, Lobo J M et al (2022). ‘Evaluating the costs of nurse burnout-attributed turnover’. Journal of Patient Safety, 1;18(4), pp. 351-357, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35617593/

NHS (2022), NHS staff survey, https://www.nhsstaffsurveys.com/results/

Nielsen K, Yarker J, Munir F, and Bültmann U (2018). ‘IGLOO: An integrated framework for sustainable return to work in workers with common mental disorders’. Work & Stress, 2;32(4), pp. 400-417, https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1438536

Pavlova A, Wang C X, Boggiss A L et al (2022). ‘Predictors of physician compassion, empathy, and related constructs: a systematic review’. Journal of General Internal Medicine, pp.1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07055-2

Raymaker D M, Teo A R, Steckler N A et al (2020). ‘“Having all of your internal resources exhausted beyond measure and being left with no clean-up crew”: Defining autistic burnout’. Autism in Adulthood, 1;2(2, pp. 132-143. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2019.0079

Rosen A, Cahill J M, and Dugdale L S (2022). ‘Moral injury in health care: identification and repair in the COVID-19 era’. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37 pp. 3739-3743, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07761-5

Taris T W, Le Blanc P M, Schaufeli W B et al (2022). ‘Are there causal relationships between the dimensions of the Maslach Burnout Inventory?’ 1;19(3):238-55, https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500270453

Tomczak M T and Kulikowski K (2023). ‘Toward an understanding of occupational burnout among employees with autism’. Current Psychology, 25:1-3, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04428-0

Van Dam A (2021). ‘A clinical perspective on burnout: diagnosis, classification, and treatment of clinical burnout’. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 3;30(5), pp. 732-741, https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.1948400

West M A and Chowla R (2017). ‘Compassionate leadership for compassionate health care. Compassion: concepts, research and applications’. London: Routledge, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315564296-14/compassionate-leadership-compassionate-health-care-michael-west-rachna-chowla

Sign up to our weekly round-up of HR news and guidance

Receive the Personnel Today Direct e-newsletter every Wednesday

Williamson V, Murphy D, Phelps A et al (2021). ‘Moral injury: the effect on mental health and implications for treatment’. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1;8(6), pp. 453-5, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00113-9

World Health Organization (2018). ‘International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (11th Revision)’, https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en