Despite working tirelessly to protect and support the health of workers during the pandemic, occupational health practitioners have often been unable to access OH services for their own mental and physical wellbeing, shocking new research has found. Dr Satish Ranka outlines the key findings.

Mental health is a state of balance between behavioural, cognitive, and emotional states. Imbalance in mental health is a significant burden as some studies estimate that one in four people may be affected (Mental Health Taskforce 2016).

Disruption to mental health can result from a number of factors including work, relationships, finance, lifestyle, health, trauma and the impact of the current pandemic (Public Health England, 2020).

Data from the UK suggests that mental health issues may be prevalent in up to 39% of employees, a rising trend compared to previous years. The Mental health at work report (2019) identified three main causes of poor mental health in employees: workload, support and ‘leavism’.

Leavism is characterised by continuing to work outside of contracted, paid hours including working during annual leave. Features may include any or all of these: a reluctance to book, or cancel annual leave; not trusting colleagues to cover work whilst away from the office and a compulsion to constantly checking emails and or completing work at home following the end of the working day.

A recent review from Italy concluded work related stress to be a cause of concern for the HCW. This is likely to increase in severity after Covid-19 was declared a pandemic in late March 2020 (Neto et al, 2020).

Expanding access to OH

CPD: Supporting nurses and their mental health in a post-Covid-19 world

Since then, the International Council of Nurses reported that 1,500 nurses have died in 44 countries as a result of this current pandemic. Such information can upset and worry people in general and health care providers in particular, including OHNs.

This has the potential to impact on their mental health and wellbeing who may then exhibit symptoms of mood disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and in severe cases suicidal ideation (González-Sanguino et al 2020; Sher 2020).

Although occupational health provision in the UK is unavailable to all workers, it is available for staff working in a variety of public and private sectors including the NHS.

Occupational health nurses are impartial advisers to both workers and employers; they practice in both the private and public sectors promoting the wellbeing of staff members whist advising and supporting their managers/employers.

The Covid-19 pandemic brought many pressures to wider UK populations, many self-employed people lost their livelihoods, possibly including self-employed OH nurses.

Other workers had been redeployed, others furloughed, and many were required to work from home.

These people, those who had contracted Covid-19 and their managers may have sought OH advice. Knowledge about the condition was rapidly changing, which increased the workload of OHNs and, for many, there was the potential for a negative impact on their mental health.

Those professionals may themselves have required OH support. Data regarding the available OH support for OHNs is not available in literature.

Hence, the author undertook a survey of amongst OHNs to establish whether or not they had access to OH services, something that was of particular importance in light of the current pandemic.

Survey methods

An online survey link was posted on a social media group with 3,800 members consisting of OH nurses, doctors and allied health professionals practising in the UK and the Republic of Ireland.

Power calculations, using Cohen effect size, suggested a minimum of 117 responses were needed to achieve for an effect size of 0.9 for this survey. Participant consent was obtained after informing them that the survey had six questions and would take less than two minutes to complete.

Participants were informed that the survey was voluntary, without incentives and no personal data would be collected.

The internet protocol addresses of the respondents captured by the survey website were immediately deleted after downloading the survey data. The survey link expired after each participant completed the survey.

Participants were aware that anonymous response data would be available to them on application to the author. The survey was checked for usability and technical functionality in a pilot study involving five healthcare professionals.

The option for participants to review their survey response was available at the end of the survey. The survey was conducted 2 months after the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK.

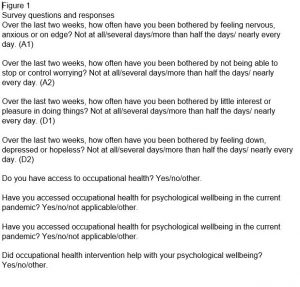

Figure 1 below shows the list of the survey questions. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4), an ultra-brief validated tool, was used to screen for anxiety and depression symptoms (Löwe et al, 2010). It had two screening questions on anxiety (A1 & A2) and depression (D1 & D2) each.

Closed questions about OH access, support, interventions and place of work were asked. Place of work was identified as NHS, independent, both and public. ‘Public’ included OHNs working with local authority, police, universities and so on. Ethical approval was sought from the NHS Health Research Authority.

Pearson’s chi-squared test of independence was used to determine the mean. The odds ratio was calculated to measure the risk differences in the workplace.

Survey results

A total of 152 OHNs responded to the survey. The average time taken by the respondents to complete the survey was two minutes.

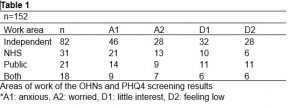

More than half (54%) of the OHNs were working in the independent sector, 20% in the NHS, 14% in the public sector and 13% in both the independent sector and the NHS.

Of these, 39% of OHNs working in the independent sector, 13% of those working in NHS, 24% working in public sector and 39% of OHNs working in both the NHS and independent sectors did not have access to OH services.

Table 1 below outlines details of the workplace and PHQ-4 screening results. Only nine OHNs accessed OH services, of which four were from the independent sector, two from NHS and three from public sector. A total of five OHNs did not find OH services intervention useful, of which three were from independent sector and two from the public sector.

PHQ4 responses suggested 32% of anxious OHNs (A1), 35% of worried OHNs, 42% of OHNs with little interest in doing things (D1) and 39% of OHNs feeling low (D2) did not have access to OH services.

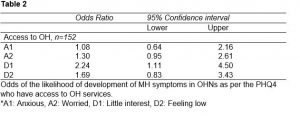

Worryingly, OHNs having access to OH services were twice less likely to develop depressive symptoms. This is shown in table 2 below.

Study discussion

This study highlights the lack of OH services support for the OHNs who look after the frontline healthcare workers and employees in private/public organisations.

The occupational health nurses were anxious, worried and feeling low and more than one-third of respondents did not have access to OH services, particularly those participants in the independent sector.

Only a small number of OHNs accessed OH services, even though significant number of OHNs were experiencing some form of anxiety and depression-related symptoms.

This survey highlights that universal access to OH is unavailable and efforts are needed to improve OH access for all employees, particularly those in the healthcare sector who are helping the frontline workers in the current pandemic.”

Equally concerning was the finding that less than half of the OHNs who accessed OH services found it useful.

The study findings suggest there may be a causal link between provision of OH services to OHNs and their mental wellbeing. Our study also highlights that access to OH for its own employees is important as it reduces the odds of development of mental health symptoms.

The importance of OH services cannot be over-emphasised because of the contribution they play in the wellbeing of the employees.

In the current pandemic, OH has been involved in risk assessment, contact tracing and supporting the mental health of employees, and this is in addition to routine services.

In many settings, OH services are generally a 9am-5pm, Monday to Friday service. During the pandemic, however, they have been significantly overstretched.

Mostly they have modified their business models to cope with the pandemic by altering their working hours, offering extended hours services, working weekends, provision of offering dedicated OH helplines and developing a purposeful Covid-19 queries inbox (Ranka et al, 2020).

However, these changes can have a significant impact on the mental health and wellbeing of the OHNs whilst, on a global scale, a search for the solution to the pandemic continues to dominate the headlines.

This survey highlights that universal access to OH is unavailable and efforts are needed to improve OH access for all employees, particularly those in the healthcare sector who are helping the frontline workers in the current pandemic.

Some of the limitations of the study include the sample size, pre-existing mental health conditions acting as confounders, a one-time measurement of exposure and outcome and the difficulty in assessing a role of a causal relationship in the development of mental health symptoms and access to OH services for the OHNs.

Measures to reduce non-response bias included a pilot study to check the appropriateness of the survey, maintaining confidentiality and sending a reminder.

It was difficult to comment on the statistical significance of OH interventions, as only a handful of the OHNs accessed OH services. The survey was conducted after the peak of the pandemic to reduce the Hawthorne effect (Payne et al, 2011).

Further studies are needed to investigate factors influencing the lack of OH access for the OHNs and the outcome of OH interventions.

In conclusion, with the ongoing pandemic situation there are challenges faced by healthcare workers both in frontline and OHNs who support them.

OHNs need OH support on planning evidence-based mental health interventions to avoid problems such as burnout, development of mood and anxiety disorders, PTSD and substance misuse to cope with and the aftermaths of the ongoing pandemic.

References

‘The five-year forward view for mental health’. A report from the independent Mental Health Taskforce to the NHS in England, 2016, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Mental-Health-Taskforce-FYFV-final.pdf

‘Possible causes of poor mental health/dealing with life’s challenges’, Every Mind Matters, Public Health England, 2019, https://www.nhs.uk/every-mind-matters/lifes-challenges/

‘Mental health at work 2019 report: Time to take ownership’, Business in the Community, Mercer Marsh Benefits (2019), https://www.mentalhealthatwork.org.uk/resource/mental-health-at-work-2019-report-time-to-take-ownership/

Neto MLR, Almeida HG, Esmeraldo JD ar et al (2020). ‘When health professionals look death in the eye: the mental health of professionals who deal daily with the 2019 coronavirus outbreak’. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112972. Available online at: doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112972

‘ICN confirms 1,500 nurses have died from COVID-19 in 44 countries and estimates that healthcare worker COVID-19 fatalities worldwide could be more than 20,000’, International Council of Nurses, 2020, https://www.icn.ch/news/icn-confirms-1500-nurses-have-died-covid-19-44-countries-and-estimates-healthcare-worker-covid

González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, ÁngelCastellanos M, et al (2020). ‘Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain’. Brain Behav Immun published online first: 2020. Available online at: doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040

Sher L (2020). ‘COVID-19, anxiety, sleep disturbances and suicide’. Sleep Med Published Online First: 2020. Available online at: doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2020.04.019

Sign up to our weekly round-up of HR news and guidance

Receive the Personnel Today Direct e-newsletter every Wednesday

Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M et al (2010). ‘A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population’. J Affect Disord 2010;122:86-95. Available online at: doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019

Ranka S, Quigley J, Hussain T (2020). ‘Behaviour of occupational health services during the COVID-19 pandemic’. Occup Med (Chic Ill) Published Online First: 14 May 2020. Available online at: doi:10.1093/occmed/kqaa085

Payne G, Payne J (2011). ‘Key Concepts in Social Research’. SAGE Publications, Ltd 2011. Available online at : doi:10.4135/9781849209397