When the Covid-19 pandemic hit last year, construction was one of the few sectors of the economy allowed to continue to working. However, as Alice Milsom outlines, the complexities, demographics, culture and working practices of the sector also meant managing and mitigating risk was challenging.

In March 2020, as we all know, a nationwide lockdown was imposed within the UK. The stay-at-home order was announced to combat the emergence of a new virus named SARS-CoV-2, otherwise known as Covid-19 (He et al, 2020). Essential industries, such as healthcare, construction, transportation and food sectors, were kept open, while non-essential industries, such as restaurants and entertainment were closed (Del Rio-Chanona et al, 2020).

The construction industry was one of the few sectors that had been allowed to continue working throughout the Covid-19 pandemic (Kale, 2020). Operating throughout the pandemic required organisations to have a robust Covid-19 risk management strategy, upholding and delivering high standards of occupational health care, whilst compliant with the government-recommended guidelines.

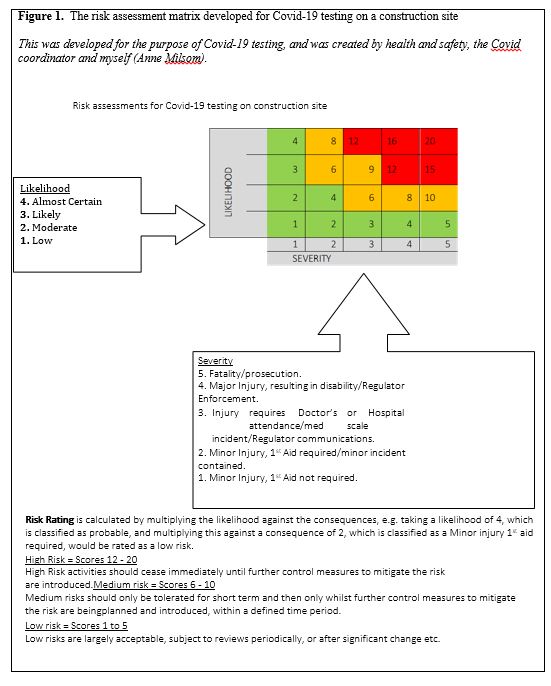

Part of this risk management strategy involved assessments being undertaken to identify the risks associated with work tasks, control measures evaluated and consistent with scientific evidence and medical and government guidelines (Health and Safety Executive, 2021).

The following year, in January 2021, the UK government and local authorities within England announced an asymptomatic testing programme. This included the provision of free testing kits for workers unable to work from home.

This testing has aimed to find individuals with active infections who are asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic in order that the chain of infection can be broken before wider spread (Rough, 2021).

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2020), however, stated that the accuracy of these lateral flow tests depended on several factors including: the time period from the onset of infection, the concentration of virus, and the reagents within the test kits.

Occupational health CPD

CPD: understanding service-area and organisational stress audits

CPD: managing stress and psychosocial risk within oil and gas

The largest variable identified was down to the person undertaking the testing procedure. Public Health England’s (PHE) investigation into the accuracy of results when carried out by different testing services highlights that there was a 79.2% accuracy rate when testing was undertaken by trained laboratory scientists, 73% when used by trained healthcare staff, but only 57.5% when conducted by self-testers. However, Torjesen (2021) states that success rates should improve with experience, especially in areas where regular testing is being carried out.

Introduction

The author, an OH nurse works for a private occupational health provider providing OH services to the construction industry. This article focuses on the compilation of a risk assessment for Covid-19 testing on a construction site.

It aims to examine the current research and literature, to ensure the risk assessment created is evidence based and to provide guidance based within recommended guidelines. The risk assessment developed (figure 1 below) gives an estimation of the likelihood of an outcome occurring but does not guarantee any outcome.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS, 2020) reveals that in 2020 2.17 million individuals within the UK were employed within the construction industry. There is a significant risk of spreading the Covid-19 within construction sites, as this sector continued to operate throughout the pandemic and tasks such as moving and handling heavy and/or unwieldy loads require working in close proximity to co-workers.

This, highlights the importance of regularly undertaking testing at construction sites ensuring the safety of the testers and site operatives.

Understanding the problem

Ensuring safety within construction is a complex activity, and is largely down to the nature of the work involved and the materials used.

Construction work involves the potential exposure to a range of anticipated physical, chemical, ergonomic, psychosocial and biological hazards, including potential exposure to a range of micro-organisms including bacteria, fungi and viruses.

The Covid-19 virus was a new microbe; this now furthered the need to keep workers and the surrounding areas safe from potential Covid-19 risks. Koh (2020) states that the nature of employees’ work may increase their vulnerability to exposure to Covid-19 and results from frequent travelling to and from the site, communal lodgings and sharing communal facilities.

However, Stiles et al (2021), argues that there is variability in the type of tasks performed, which will impact the degree of risk. An example of this is whether the workers are undertaking their work tasks indoors in poorly ventilated spaces or outside in the open air where ventilation is much better. Based on risk and current guidelines, those working indoors are at much greater risk than those undertaking similar work tasks outdoors.

The construction sector was amongst the first affected by Covid-19 (Koh, 2020) and has been affected by a high rate of infection (ONS, 2020).

There are several contributory factors that underpin this level of infection and the outcome of such infection. Esteve et al (2020) identifies that age is a significant factor to be considered when addressing outcome risk. According to the ONS (2018), the construction sector has an ageing workforce, with more than 40% aged over 40 years.

A significant number of these workers are older workers aged over 55. In the case of any pandemic disease or injuries, especially respiratory causes, older workers are more susceptible to being affected. This puts these individuals at higher risk of developing complications associated with Covid-19 infection (Dhama et al, 2020).

Furthermore, data released from the ONS (2021) found that the highest incidence of positive cases were found in people aged between 35 to 49 years. With the construction sector employing many within this age group, it was essential to ensure effective measures are in place.

Wells et al (2020) identifies further compounding factors, they highlight that within this sector there is a large proportion of workers are of Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) heritage. Preliminary statistics suggest that a significant proportion of the migrant workforce has been disproportionately affected by Covid?19. This may also be reflective of their living conditions, in which they live in close proximity to each other.

Organisational change and management

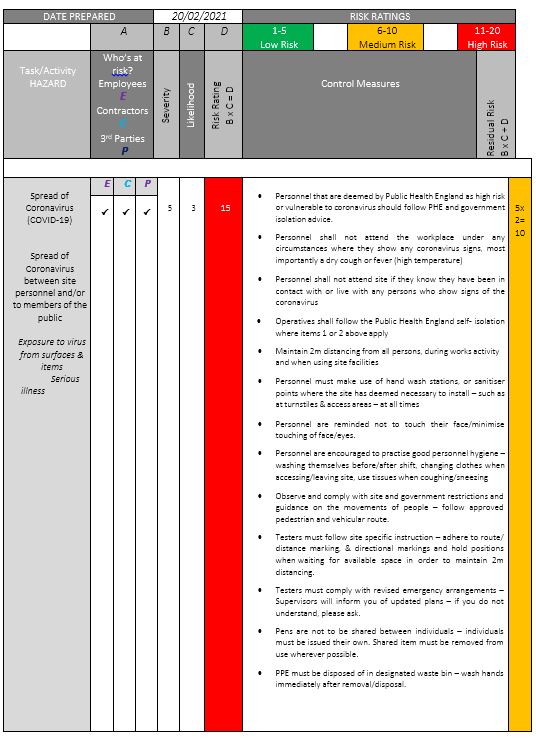

The author is employed by an organisation tasked to manage and reduce Covid-19 cases on construction sites. Control measures were introduced with the aim of protecting employees from contracting and transmitting Covid-19 whilst attending their place of work.

The author and the organisation highlighted lateral flow antigen testing to be an important strategy to track infection and prevent transmission within this environment. This sits alongside a detailed risk assessment method statement (RAMS) that was evidenced to be a cost-effective way to screen and monitor employees in relation to infection with Covid-19.

Mina et al (2020) emphasises that testing asymptomatic individuals is vital in detecting individuals who are likely to be infectious. Furthering this, He et al (2020) state that this method of screening is one of the most promising tools to control Covid-19 infection rates. The study of Wells et al (2020) identify that one in five people who are Covid-19-positive do not display any signs or symptoms, thus reinforcing the importance of Covid-19 mass testing.

Viral infections have been a part of day-to-day life for centuries (Grubaugh et al, 2019). However, studies on seasonal influenzas have shown a negative impact on employee health and business productivity, thus leading to increases in absenteeism within businesses (Ip, 2015).

Combining this knowledge with evidence arising from Covid-19, it is apparent that occupational change and leadership must be implemented to ensure business performance is maintained. Donthu and Gustafsson (2020) identifies that businesses can implement small changes to ways of working which can help protect employees and ensure safety, these changes include: reducing face-to-face meetings, virtual webinars, screening tools, temperature checking and testing services.

Zhang et al (2020) agrees that the companies which implement these changes are likely to reduce the impact of Covid-19 on the running of the business. However, it can be argued that changes made to ways of working pose a significant challenge for businesses. Changes within such organisations are often met with poor feedback, resistance to change and personal and organisational resilience might be adversely affected. These are important considerations when leading change, particularly when implementing new ways of working (Robertson et al, 2015).

Occupational health intervention

The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in the OH sector undergoing huge changes throughout 2020 (Ranka et al, 2020). Covid-19 has led to services having to embrace agile learning to adapt to legislative changes, rapidly changing government guidance and the impact on working norms.

This has been a challenge for OH services as they have had to ensure that the correct advice and appropriate support is implemented in order to maintain employee safety.

Covid-19 has led to services having to embrace agile learning to adapt to legislative changes, rapidly changing government guidance and the impact on working norms. This has been a challenge for OH services.”

Ratten (2020) states that, with continuing research and studies into Covid-19, advice is changing. Section 6 of the NMC Code of Conduct, (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018), highlights that practice should be in line with the best available evidence. Throughout the pandemic, the knowledge base has evolved and practices have changed in line with this. In addition, risk assessments, monitoring and updates were required regularly.

One of the main interventions was the setup and running of Covid-19 lateral flow testing, which was implemented on construction sites across the UK. This was instigated alongside other key strategies for containing outbreaks including; pharmaceutical counter measures (for example, vaccines), public health interventions (for example, social distancing and infection control strategies, including the use of alcohol gels, face covering and maintaining space between people.

These strategies included symptom monitoring, hygienic measures and reporting, and case isolation (Zheng et al, 2020). In addition, OH services assisted with workplace policies such as flexible working, staggered shifts and sickness absence policies. Self-employment is a feature of the construction industry, particularly among trades such as electricians and plumbers.

Between 2014 and 2016 an estimated 41% of employees working in construction were self-employed. This is a significantly higher proportion compared to other sectors, where it is estimated that only 15% are self-employed (ONS, 2018). This is also significant as those who are self-employed do not qualify for sick pay or other employee benefits (Adams-Prassl et al, 2020).

In the context of Covid-19, this poses a significant risk to transmission rates, as self-employed contractors will be unpaid if they test positive and are then required to quarantine, with the potential to pose challenges for lateral flow testing and impacting negatively on the validity of site testing.

Risk assessment/findings

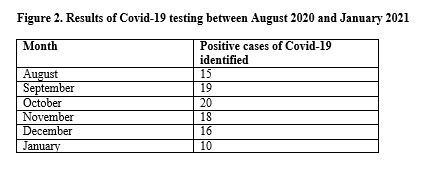

Since the implementation of the lateral flow testing service, alongside the risk assessment, the data correlated in figure 2 (below) identifies a reduction in cases, higher levels of attendance and overall lower transmission rates.

On completion of the Covid-19 testing risk assessment, the author and the health and safety manager examined potential barriers on actioning the risk assessment.

As the author progressed through the implementation of the risk assessment, it was apparent that to enforce this, a number of actions were required.

This involved agreement and cooperation from all areas of the sites. The author understood that the organisational history of construction sites could be a considerable barrier to reducing risk for employees. Nearly all projects within the industry are delivered through joint working of multiple organisations (Lizarralde et al, 2011). There are usually multiple companies, contractors, subcontractors and a supply chain, making this a barrier in getting clear guidance and risk assessments followed and implemented on sites.

One potential issue the author acknowledged, was the nature of the workers personal lives. A Construction Industry Training Board (2018) report states that, in order to remain employed, around 35% of contractors live away from home.

The nature of construction therefore results in workers frequently lodging together, staying in hotels and were not returning to set addresses daily.

This meant that the risk assessment had to be clear in identifying potential hazards to ensure that those testing for Covid-19 were not exposed to high-risk workers. Another critical aspect is the protection of the employees and testers who are deemed as high risk workers; this was defined by the UK government as including individuals aged 50 years and above, and those with systemic diseases resulting in them being considered as having disabilities (Ahmed et al, 2020).

Taking this into consideration, the author suggested that, once these individuals are identified, individual risk assessments and occupational health assessments should be conducted to prevent further risk.

Epidemiology, demographic and leadership all play a vital part when identifying high-risk work areas plus individuals and groups of workers at risk”

Control measures designed to reduce the spread of infection included one-way systems, reduction in contact and making the risk assessment available to all; overall risk of transmission whilst onsite should be low. Murnane et al (2016) agrees that appropriate communication, leadership and a robust risk assessment, can raise awareness and therefore, can reduce risk.

Further findings suggested that education is paramount when implementing a successful risk management strategy. Shalev et al (2014) report optimism bias to be present in certain individuals, this is a common concept which is deemed as a barrier to successful risk management.

This theory is based upon the idea that individuals believe they themselves are less likely to experience a negative event compared to others, although the risk maybe the same. Education, therefore, is essential in the implementation of OH strategies and may be a significant factor in influencing the workers’ assessment of the threat to their health and wellbeing.

To ensure that all employees and Covid-19 testers are appropriately educated in the risk, the OH service developed health education interventions that incorporated material including information about the virus. This outlined that the routes of transmission included inhalation of droplets or aerosols and that people may also become infected as a result of touching surfaces that have been contaminated by the virus then touching their eyes, nose or mouth without first having cleaned their hands by washing or the application of alcohol sanitising fluid.

This information was supplemented with details of the signs and symptoms of Covid-19 infection, categories of workers that may be particularly vulnerable and treatment and management protocols (Van Seventer and Hochberg, 2017).

It was considered important that testers should also be similarly adequately trained and given information of the types of personal protective equipment (PPE) that should be worn and their proper use. It was also important that workers understood the importance of appropriate cleaning, storage and disposal of such PPE. In addition, guidelines for all testing were issued to protect workers and prevent viral transmission.

Conclusion

Implementing a risk assessment and risk management strategy to fit with the business needs whilst upholding current guidance and practice proved challenging during the Covid-19 pandemic. As risk assessments should be evidence based (Desmarais, 2017), carrying out an assessment of risk on a largely unknown virus was an arduous task.

It is it an essential part of occupational health to establish and appropriately respond to particular risks and specific health needs to help prevent ill health or injury (Royal College of Nursing, 2016). With new evidence and research developing, this risk need assessment had to be altered to fit changing practice.

It is important to acknowledge the importance of research and knowledge when implementing risk assessments within a risk management strategy.

Furthermore, epidemiology, demographic and leadership all play a vital part in their success as these are essential when identifying high-risk work areas plus individuals and groups of workers at risk was acknowledged.

Initiating this risk management approach was reflected in a reduction in positive cases despite frequent changes to guidance from the government, coupled with the potential for resistance to changing behaviours.

Sign up to our weekly round-up of HR news and guidance

Receive the Personnel Today Direct e-newsletter every Wednesday

References

Adams-Prassl A et al (2020). ‘Inequality in the Impact of the Coronavirus Shock: New Survey Evidence for the UK’. Available at: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/305395/cwpe2023.pdf?sequence=1

Ahmed N et al (2020). ‘Tobacco smoking a potential risk factor in transmission of COVID-19 infection’, Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(4), pp.104.

Construction Industry Training Board (CITB) (2018). ‘Fuller working lives in construction’. Available at: https://www.citb.co.uk/documents/research/fuller-working-lives-in- construction.pdf

Del Rio-Chanona R at al (2020). ‘Supply and demand shocks in the COVID-19pandemic: an industry and occupation perspective’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(1), pp.94-137.

Desmarais S (2017). ‘Commentary: Risk Assessment in the Age of Evidence-Based Practice and Policy’, International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 16(1), pp.18-22.

Dhama K et al (2020). ‘Geriatric Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Problems, Considerations, Exigencies, and Beyond’, Frontiers in public health, 8(5), pp.1-7.

Donthu N and Gustafsson A (2020). ‘Effects of COVID-19 on business and research’, Journal of business research, 1(17), pp.284-289.

Esteve A et al (2020). ‘National age and coresidence patterns shape COVID-19 vulnerability’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 117(28), pp.16,118-16,120.

Grubaugh N D, Ladner J T, and Lemey P (2019). ‘Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty- first century’, Nat Microbial, 4(3), pp.10-19.

He X et al (2020). ‘Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19’. Nature Medicine, 26(5), pp.672-675.

Health and Safety Executive (2021) ‘Managing risks and risk assessment at work’. Available: https://www.hse.gov.uk/simple-health-safety/risk/index.html

Ip D et al (2015). ‘Increases in absenteeism among health care workers in Hong Kong during influenza epidemics, 2004-2009’, BMC Infect Dis, 15(2), pp.586.

Kale R (2020). ‘Impact of COVID-19on infrastructure and environment’, Purakala, 31(37), pp.98-105.

Koh D (2020). ‘Occupational risks for COVID-19infection’, Occupational Medicine, 70(1), pp.3-5.

Lizarralde G, de Blois M, and Latunova I (2011). ‘Structuring of Temporary Multi-Organisations: Contingency Theory in the Building Sector. Journal of Project Management. 42, pp.19-36.

Mina M J, Parker R, and Larremore D B (2020). ‘Rethinking Covid-19 test sensitivity – A strategy for containment’, New England Journal of Medicine, 38(22), pp.120.

Murnane R, Simpson A, and Jongman B (2016). ‘Understanding risk: what makes a risk assessment successful?’, International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment. Available at: https://www.unisdr.org/preventionweb/files/49584_ijdrbe0620150033.pdf

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2018). ‘The code: Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates’. London: Nursing & Midwifery Council.’ Available at: https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/

Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2018). Migrant labour force within the construction

industry: June 2018. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationa lmigration/articles/migrantlabourforcewithintheconstructionindustry/2018-06-19

Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2020) ‘Construction output in Great Britain: September 2020, new orders and Construction Output Price Indices, July to September 2020 Statistical Bulletin: UK Labour Market’. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/constructionindustry/bulletins/construction outputingreatbritain/september2020newordersandconstructionoutputpriceindicesjulytosepte mber2020

Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2021) Coronavirus (COVID-19) weekly insights: latest health indicators in England. Available at : https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/coronaviruscovid19weeklyinsights/latesthealthindicatorsinengland12february2021#:~:text=Even%20though%20more%20young%20people,aged%2065%20years%20an d%20over

Ratten V (2020). ‘Coronavirus and entrepreneurship: changing life and work landscape’, Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 32(5), pp.503-516.

Robertson I, Cooper C, Sarkar M, and Curran T (2015). ‘Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: A systematic review’, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(3), pp.533-562.

Ranka S, Quigley J, and Hussain T (2020). ‘Behaviour of occupational health services during the COVID-19 pandemic’, Occupational Medicine, 70(5), pp.359-363.

Rough E (2020). ‘Coronavirus: Testing for Covid-19’. London: House of Commons. Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8897/

Royal College of Nursing (RCN) (2016). ‘Nurses 4 Public Health The Value and Contribution of Nursing to Public Health in the UK: Final Report’. Available at: https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-005497

Shalev E et al (2014). ‘Optimism bias in managing it project risks: a construal level theory perspective’. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/301362289.pdf

Stiles S, Golightly D, and Ryan B (2021). ‘Impact of COVID?19 on health and safety in the construction sector’. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries.

Torjesen I (2021). ‘Covid-19: How the UK is using lateral flow tests in the pandemic.’ BMJ, 287. Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n287.long

Van Seventer J and Hochberg N (2017). ‘Principles of Infectious Diseases: Transmission, Diagnosis, Prevention, and Control’, International Encyclopaedia of Public Health, (2)3, pp. 22-39.

Wells P et al (2020). ‘Estimates of the rate of infection and asymptomatic COVID-19 disease in a population sample from SE England’. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33068628/

World Health Organization (2020). ‘SARS-CoV-2 antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic tests: an implementation guide’. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017740

Zhang M, Shi R, and Yang Z (2020). ‘A critical review of vision-based occupational health and safety monitoring of construction site workers’, Safety science, 12(6), pp.46-58.

Zheng H Y et al (2020). ‘Elevated exhaustion levels and reduced functional diversity of T cells in peripheral blood may predict severe progression in COVID-19 patients’, Cellular & molecular immunology, 17(5), pp.541-543.