The impact of furlough, shielding, home working and sickness absence because of Covid-19 itself have, unsurprisingly, dominated the health and wellbeing agenda for the past 16 months. Yet, as we look now beyond the pandemic, James Grindlay argues OH will need to respond to massive unaddressed issues around absence, sickness and presenteeism that predate the pandemic and have not gone away.

The impact the Covid-19 pandemic has had on sickness absence – in other words, those taking time off from work due to illness – cannot be underestimated: 39% of companies have included the virus among their top three causes of short-term absence while a further 16% suggest that it has been the cause of a lengthier off period.

Sickness absence

Will Covid-19 change how we think about sickness absence?

Sickness absence at 15-year low

Mental ill health accounted for more than half of sickness absence in last year

Meanwhile, mental ill health remains the number one cause of long-term absence, followed by musculoskeletal injuries and stress. However, absentee figures have not always occurred in the way that employers might anticipate. Indeed, by certain metrics, the overall rate of people calling off work has actually fallen. How could this be?

The pandemic has greatly affected absence data in a number of complex and contradictory ways. While it is certainly true there is an increased absence because of the virus itself, a number of governmental measures, such as the furlough scheme, greater social distancing and a vast uptake in the number of people working from home, have all meant that the general trend has been one of fewer recorded absences.

The impact of furlough

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) found in its retention scheme statistics that, as of the 15 February 2021, the number of jobs furloughed reached 11.2 million, with 1.3 million employers opting to use the scheme at a total cost of £53.8bn. These are astonishing numbers: however, these figures do not tell the full story – many of those furloughed did not remain so for long.

Beginning from its announcement on 20 March, 2020, up to 4.8 million employees took up the scheme by the 23 March, rising to 6.8 million by the end of that month and peaking at 8.9 million by 08 May, 2002. Since that early peak, the number of people furloughed has seen a gradual but substantial decline, albeit with temporary spikes in the winter months.

As of 31 January, 2021, the figure stood at 4.7 million, with a considerable decline imminent as the scheme draws to a close in September.

The impact of shielding

As part of the precautionary measures in tackling the pandemic, the NHS drafted a ‘Shielded Patient List’ as part of an assessment of those most vulnerable to the virus. These individuals were asked to stay at home and protect themselves or ‘shield’.

It should be noted this group, being particularly at risk, would also have been far more likely to call in sick for pre-existing conditions had they not been requested to stay at home.

Their homebound status over the past 18 months could well be one the major factors for the reduction in the sickness absence rate that we have seen in 2020.

The impact of working from home

A study from the Office for National Statistics in 2020 found that a vast number of people, mostly those in office-based jobs, were becoming more and more accustomed to working from home.

According to its results, 86% did so as a direct result of the Covid-19 pandemic. As of April 2020, up to 46.6% of people in employment did at least some of their work from home; approximately one-third (34.4%) worked fewer hours than usual, whilst another 30.3% reported doing more hours than they otherwise would.

The figures in London were far greater than the national average, with more than half of London residents (57.2%) spending their working hours in the home.

What has this meant for sickness figures?

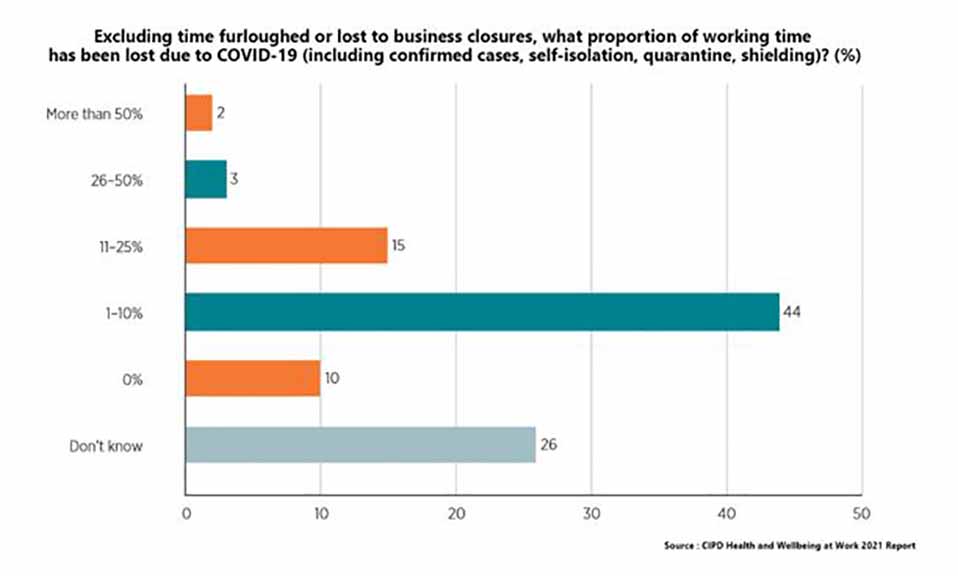

The figure below, from The Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development (CIPD), shows the impact of the pandemic in terms of time lost to Covid-19 for things such as sickness absence, self-isolation, shielding and quarantining.

Each of these factors has had a significant corollary effect: less exposure to everyday germs and viruses through increased social distancing, shielding, working from home and living in isolation have meant that the instances of day-to-day virus transmission (in other words, non-Covid) has seen a sharp decline.

Of special note is those employed but on furlough – they are included in the denominator for the number of days lost per worker but would not be contributing to the numerator.

So far so good. Or is it? The results indicate a significant drop-off in sickness absence (in fact the lowest since records began in 1995) yet, since there are so many ameliorating factors, they may give a highly distorted picture of what we might expect now that lockdowns – and their attendant restrictions – are easing.

Those who have not experienced the luxury of the aforementioned measures may be a stronger indicator for what is to come. Consider key workers, who have carried on with their jobs throughout the last 18 months with little or no respite.

In particular, let us consider the impact upon health and social care professionals, as well as those who work in public safety and national security. They have seen a surge in their sickness absence from 2019 to 2020 of 2.9 to 3.5 (days of absence per worker) and 2.0 to 2.7, respectively.

Whilst it may be expected that healthcare professionals in particular have a higher rate of absence because of their prolonged exposure to people with illness, the real story is that of public safety and national security personnel.

In 2019, these individuals placed significantly below those in education and childcare and employees in local and national government, both at an average of 2.4 absence days per worker. Yet, their 0.7 leap from the previous year marks the single largest change out of all key worker demographics. Indeed, this huge sudden upturn has meant they are now second only to health and social care professionals in their number of absences.

Are we headed towards a sickness absence pandemic?

Whether or not the case of public safety and national security personnel can be treated as a predictor for those in other fields coming out of the pandemic remains a point of speculation.

What we do know, however, is that, as restrictions ease, there will doubtlessly be an intensification of common ailments that were once widespread pre-pandemic. How businesses respond to the changing circumstances – especially the number of people allowed to continue working from home – will ultimately determine trends for the next 18 months.

Thankfully, it would appear that employers have already begun to recognise the problems on the horizon, particularly with regards to mental health and wellbeing.

The response of businesses

According to the CIPD’s ‘Health and Wellbeing at Work Report’, published in April this year, a number of proactive measures are in the process of being implemented across the board.

Among its findings are three key areas that have seen significant progress: an increased emphasis on employee wellbeing, an improvement in the way senior leaders are trained and a more individualised, tailored support network.

The impact of the pandemic has seen wellbeing rise rapidly up the corporate agenda. The number of employees who consider their organisation ‘much more reactive than proactive’ with regards to mental health and wellbeing has dropped dramatically, from 41% last year to 27%.

Meanwhile, a smaller yet no less significant number of respondents have signalled that their place of work has put into practice a formal wellbeing strategy (44% to 50%).

Meanwhile, an impressive 75% of respondents believed their senior management staff had employee wellbeing high on their agenda, an increase of 14% from the previous year. In addition, two-thirds suggested that their line managers are more clued-in to the importance of their personal wellbeing in comparison to 2020 (58%).

As yet another consequence of the coronavirus outbreak, more and more organisations are pursuing bespoke solutions to individuals’ mental and physical health. Employee assistance programmes, counselling services and management referrals have been crucial in this regard, with numbers likely to increase once lockdown restrictions have been fully lifted.

The ongoing role of occupational health

Although it appears as though companies are moving in the right direction, there is still much more work to be done.

Access to support services for people with a disability or long-term health condition still has a great capacity for improvement. To take but one instance, such workers report an increase in the development of line manager knowledge and confidence is their most sought-after area of improvement (50% of respondents). Yet less than a third of businesses provide adequate training and guidance.”

Access to support services for people with a disability or long-term health condition still has a great capacity for improvement. To take but one instance, such workers report an increase in the development of line manager knowledge and confidence is their most sought-after area of improvement (50% of respondents). Yet less than a third of businesses provide adequate training and guidance.

To take another example, an overwhelming majority of respondents to the CIPD survey reported examples of presenteeism (formal attendance but reduced capacity to work) and leaveism (using allocated annual leave to take time off not for holidays and other social events but because of being unwell) at 84% and 70% respectively.

Often the two coincide; individuals suffering from underlying health conditions may simply try to carry on regardless, only taking days off when they feel they absolutely have to, and then using their allotted holiday time instead of being forthcoming with their condition. Indeed, 79% of respondents that observed presenteeism also acknowledged leaveism in their place of work.

Figures such as these heavily suggest that there are, in spite of improvements, serious unaddressed issues that occupational health services could otherwise resolve.

An increased awareness, sense of openness and higher degree of professional training are absolutely necessary for us to evolve both as an economy and as a culture.

Sign up to our weekly round-up of HR news and guidance

Receive the Personnel Today Direct e-newsletter every Wednesday

For although we cannot undo the pandemic itself, we can, at the very least, learn from it.

References

CIPD (with Simplyhealth) Health and Wellbeing at Work 2021, April 2021,

https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/health-wellbeing-work-report-2021_tcm18-93541.pdf

Coronavirus job retention scheme statistics: February 2021, HMRC, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/coronavirus-job-retention-scheme-statistics-february-2021/coronavirus-job-retention-scheme-statistics-february-2021

Coronavirus and homeworking in the UK: April 2020, Office for National Statistics, July 2020, https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/coronavirusandhomeworkingintheuk/april2020