Ethical leadership, trust and equality are seen as important qualities for successful organisations. But many would argue populism entails a style of leadership totally at odds with modern HR thinking. Adam McCulloch examines how employees are affected by the contrast between national and company leadership.

Contemporary business practice emphasises the rational and the compliant. The long-term interests of organisations are seen as best-served if leaders and employees behave ethically with diverse boardrooms that can avoid the pitfalls of “groupthink”.

In no previous era has more value been placed on equality, inclusion, fairness and transparency; we now have gender pay gap reporting, may soon have ethnicity pay gap reporting and the advent of unconscious bias training has spawned myriad consultancies led by psychologists whose names are followed by a string of letters.

Yet paradoxically society appears more divided than ever and, strikingly, we are electing and rewarding “populists”; leaders who express views that condemn and offend large groups of people and/or make whimsical decisions based on short-term interests rather than for the long-term common good. Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, Jeremy Corbyn and Boris Johnson has each been accused of racism, self-interested behaviour and mendacity in recent times.

Rob Briner, professor of organisational psychology, Queen Mary University of London, puts it like this: “If organisations are expecting employees to treat their colleagues equally and fairly it may get increasingly harder if the leaders in wider society are doing something quite different – and are apparently being rewarded for it.” Or, to be more succinct: “Do people at Trump rallies go on diversity training courses the next day?”

Broadcaster Steve Richards, speaking on BBC Dateline London last week, raises a related issue: “The election of Trump has given permission for people with epic flaws to become leaders.”

Leadership

It seems there is a growing tension between what we expect of leadership in organisations and what we expect of our national leaders. As Briner implies, if that tension increases much further, HR may have to anticipate some significant changes in employee and management behaviour.

He says: “The question of how can we expect employees to ‘do the right thing’ when our leaders don’t is fascinating. There is a general sense people in authority positions are essential as role models – we tend to copy or at least understand what kind of behaviour is acceptable or unacceptable from the way our leaders behave. So leaders behaving badly might encourage others to do the same.”

And, of great pertinence in the era of Trump, Brexit and the immigration debate, “there’s certainly a view that those who hold xenophobic or racist attitudes feel emboldened to express those views if those in leadership positions seem to hold similar attitudes”.

The question of how can we expect employees to ‘do the right thing’ when our leaders don’t is fascinating” – Rob Briner

Is it the case that we tacitly accept that leaders play by a different set of rules and don’t have to comply? Do we secretly admire the liars and the ruthless game-players, quietly recognising that our own lives are made more comfortable by us being compliant, honest and hardworking?

‘Dark traits’ and the case for ethical leadership

The CIPD recently produced a report that challenges this idea. The study, Rotten Apples, Bad Barrels and Sticky Situations: a review of unethical workplace behaviour, found that “moral leadership and ethical climate and social norms enhance ethical behaviour”. It argues that regulatory developments such as the Financial Reporting Council’s Corporate Governance Code, Senior Managers’ Regime, Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority, Banking Standards Board, Financial Conduct Authority etc, show that there is now a concerted attempt to normalise, embed and enforce higher standards of ethics in business.

Could it be then that our notions of leadership, where we are prepared to tolerate braggarts, narcissists and charlatans for the sake of charisma, is outmoded?

According to the CIPD report just under a third (31%) of people professionals say that managers in their organisations often demonstrate unethical behaviour, and a large minority of people professionals (28%) find themselves in positions where the organisation’s expectations are at conflict with their professional beliefs. The report states: “Senior leaders should reinforce positive norms by role-modelling ethical behaviour and through the messages they communicate. Employees are more likely to act unethically when they perceive their organisation to be unfair: for example, if reward isn’t shared fairly, or policies are inconsistent.” This, surely, is a warning for those happy to tolerate Trumpian leadership.

But we aren’t automatons; it is hard to see how we can all fit into such a fair and ethical organisational culture given our individual personality traits. Psychologists often refer to “dark triad personalities”. The CIPD report’s authors, Jonny Gifford and Melanie Green, state that “These tend to enhance competitiveness, by inhibiting cooperation and altruistic behaviours at work,” thus they damage the organisation.

Senior leaders should reinforce positive norms by role-modelling ethical behaviour and through the messages they communicate. Employees are more likely to act unethically when they perceive their organisation to be unfair” – CIPD report

Personnel Today recently published a light-hearted piece by Pearn Kandola’s head of development Stuart Duff on the lessons for HR of Game of Thrones. The characters of Tywin and Cersei Lannister, with their constant manoeuvrings were, said Duff, “incredibly destructive and unsustainable. They exhibit a style of leadership that will ultimately alienate those around them” and “risk sowing the seeds of their own demise”.

The CIPD report makes a similar point while referring to the most famous game-player of them all: “People high on Machiavellianism tend to have a disregard for morals, and a strong willingness to manipulate and deceive others. Narcissism is related to high levels of pride, low levels of empathy and high ego … psychopathy relates to impulsive, anti-social behaviour and lack of remorse.” The authors advise leaders to “avoid pitting employees against each other and keep promotion processes fair and transparent”.

These insights make it clear that dark traits are not beneficial for organisations that need to present an ethical face to markets and regulators, and surely it’s self-evident that for good morale and working relationships to be maintained, a strong ethical core must run throughout the business.

John Hackston, head of thought leadership at The Myers-Briggs Company tells Personnel Today: “It’s certainly nothing new to see leaders as tough and aggressive. While these characteristics may help individuals climb the greasy pole, they do not necessarily help organisations prosper.”

For Hackston there is evidence that “organisations perform better financially when managers are less aggressive and more agreeable. This may be bad news for organisations with a ‘disruptive’ leader.”

He prefers to view personality through a prism that emphasises modes of responses rather than fixed traits, and says: “We know that people at higher levels in organisations are more likely to have preferences for Thinking [the Myers-Briggs personality type]. This can mean they neglect focusing on people and when they become stressed, they may neglect it even more.” He argues that this can lead to a tendency for leaders to ignore the ethical dimension.

“Where there is less diversity of personality within a team, ‘groupthink’ may occur and less balanced decisions are made. There is also research which reveals teams with narcissistic leaders perform poorly for this very reason, as the leader not only doesn’t listen to their team members, but their influence actively suppresses team members sharing ideas with each other.”

Yet the narcissists and Machiavellis have been making it to the top on a regular basis. In Why Bad Guys Win at Work, published in the Harvard Business Review, business psychologist Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic writes that “narcissists are often charming, and charisma is often the socially desirable side of narcissism: Silvio Berlusconi, Jim Jones, and Steve Jobs personified this”. He describes how a study of German businesses positively linked narcissism with higher salaries, while Machiavellianism was positively linked to leadership level and career satisfaction.

Where there is less diversity of personality within a team, ‘groupthink’ may occur and less balanced decisions are made. There is also research which reveals teams with narcissistic leaders perform poorly for this very reason” – John Hackston, The Myers-Briggs Company

He quotes criminal psychologist Robert Hare’s delightful line: “Not all psychopaths are in prison – some are in the boardroom.” Further academic studies lead him to conclude, shockingly, that “the base rate for clinical levels of psychopathy is three times higher among corporate boards than in the overall population”.

Toxic leaders are our responsibility

Such findings may not exactly inspire employees to perform ethically and comply with organisation values. It is easy to see how insider trading, illegal phone tapping, false accounting and devious career manoeuvring will prosper if the rewards are seen as higher. US business theorist Jeffrey Pheffer, writing in Fortune, agrees with Chamorro-Premuzic that leadership too often goes hand-in-hand with negative characteristics, but points to our own responsibility as members of society to change matters: “It is only when we stop making excuses for ‘toxic leaders’ that things will change. Trump has many of the leadership characteristics we say we abhor even as we reward them.”

Thankfully there are more decent characteristics that leaders share, say the CIPD report authors: “Some individuals place more value on concern for peers or stakeholders, regardless of circumstance, whereas others take a situational view. Research suggests that those who value honesty are more likely to act in an honest way, in part to maintain their positive self-image.”

And Pearn Kandola’s research on leadership leads Duff to question the mirroring effect that many say results from unethical leadership: “Interestingly, not one of the leaders that we interviewed talked about the influence of high-profile leaders in business or society – such as Donald Trump – later in life. Once we have established our self-identity and our personal values, it is highly unlikely that the behaviour of public figures will significantly change these.”

The research conducted by the firm found that leaders, when asked about those who inspired them, often referred to significant individuals who had a strong influence early in their lives. They would typically be a parent, carer, a family member, a close friend or a member of the community and would have offered a mixture of honest guidance, support and inspiration to achieve. Duff says: “We heard about teachers who inspired, church leaders who challenged and siblings who set an example through their behaviour and performance. In every case, these significant role models shaped the opinions and attitudes of the leader and encouraged them to reflect on their personal moral standards and judgments.”

Once we have established our self-identity and our personal values, it is highly unlikely that the behaviour of public figures will significantly change these” – Stuart Duff, Pearn Kandola

He strikes a positive note about today’s corporate leaders: “It’s tempting to stereotype CEOs and senior leaders as ‘psychopaths’ or ‘narcissists’ who are out to achieve regardless of the cost, but that is the exception and not the rule. Most CEOs and their executive team will be very conscious of how their behaviour will be judged, both in terms of performance and ethics. We would challenge the belief that ambitious people are rule breakers per se. Even those who describe themselves as disruptors and ‘rule-breakers’ are not necessarily unethical in approach. They may simply describe themselves as being less structured and more flexible in the way that they work and interpret the rules.”

Ethical progress and expectations

Elva Ainsworth, CEO and founder of consultancy Talent Innovations says the potency of leadership is diluted without an ethical code: “It is clear that the ethics of our leaders is critical – the perceived integrity of those in charge is important for the maintenance of a good brand but it is also fundamental as a foundation of powerful leadership.”

HR Director opportunities on Personnel Today

She underlines the progress we’ve made towards a more ethical culture: “The standards we expect to live by have shifted. The standards by which we relate to discrimination for instance are remarkably different. Years ago we would not expect to see women at board level. I was told I could not wear trousers in my first jobs – this was the 1980s. I was told clearly that ‘women don’t apply for these type of jobs’ in a formal interview with a respected company. These positions were not considered unethical at all back then.”

This progress has been too fast for some, she adds: “It’s always painful when standards have moved but not everyone has quite caught up with it. It may appear that leaders are unethical but actually our society is getting more particular and demanding.”

The tension between our expectations of leaders in the political arena and our preferences in our workplaces can also be explained by “distance”, says Kate Cooper, head of research, policy and standards at the Institute of Leadership & Management. She says: “People judge national leaders in a different way than organisational leaders – and it’s because of distance. They can only guess at their ethical qualities and don’t have the same expectations. Whereas organisational leaders are people you know; in the same way, line managers are trusted more than CEOs.”

But, she says, amplifying the CIPD report and Briner’s point, there is a real danger of workplace behaviour being influenced by unethical leaders within the organisation and further afield: “It’s well documented that behaviours are mirrored… ‘we all lie and cheat here’ – just look at the MPs’ expense scandal.”

People judge national leaders in a different way than organisational leaders – and it’s because of distance. They can only guess at their ethical qualities and don’t have the same expectations” – Kate Cooper, Institute of Leadership & Management

She adds: “We want to fit in as humans; not fitting in is uncomfortable and anxiety-causing.” However, people do hold politicians to a slightly different standard she adds. “We expect MPs to have autonomy… politicians exist in a freer space.”

The results of unethical leadership

The results of favouring charisma and “strong leadership” over ethical values and rules-based governance can be devastating for organisations. As Chamorro-Premuzic writes, the “success of the bad guys comes at a price, and that price is paid by the organisation”.

The CIPD points to the many forms this price can take: “From misreporting of profit and loss (Enron and Fanny Mae), to sexual misconduct and safeguarding issues (Oxfam and the #MeToo movement), manipulation of interest rates (Libor) and diesel emissions (Volkswagen et al), misselling of insurance (PPI), noncompliance with safety standards (BP and Halliburton Deepwater Horizon environmental disaster), substandard healthcare (Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust) and tax evasion and avoidance (the Panama Papers)”.

The authors recommend that regardless of individual differences, such as levels of performance, “leaders must be clear on their organisation’s ethical code of conduct and take their role seriously in cascading clear guidelines on what constitutes acceptable behaviour and what does not.” They point out that moral reminders (such as pointing to an ethical code of conduct) can be effective in minimising unethical behaviour and that HR needs to take a role in targeting “high-risk teams”, those which contain high-pressure roles.

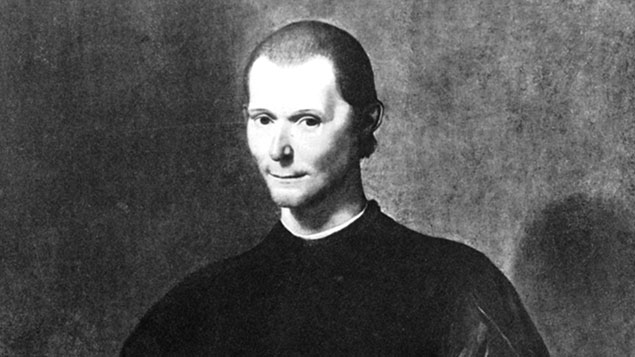

Portrait of Niccolo Machiavelli, whose name is used by psychologists to describe certain dark personality traits.

PA Images

Perhaps it is not unthinkable that employees, imbued by ethical thinking and the desire for moral leadership, reject those whose values do not reflect their own, even those in elevated positions. The recent cancelled invitation of journalist/campaigner Julia Hartley-Brewer to address doctors is quite instructive.

The Royal College of GPs’ letter to Hartley-Brewer withdrawing her invitation to speak, stated: “It has become clear that some of the views she has expressed are too much at odds with the core values of Royal College of GPs and our members, and our work to promote inclusivity within the profession and among patients … her views are divisive, hateful and do not represent the diversity the medical profession represents.”

For many, this is a free speech issue and a dangerous precedent, but it cannot be denied it is a strong expression of employees’ values. Perhaps it’s not a stretch to argue that, in some organisations, such a strong ethical value base has been created that the leaders themselves are subject to it, rather than being something they set.

Do women make more ethical leaders?

Briner suggests there may be a gender dimension to the issue: “It may be that in some senses we sort of want our leaders to be bad boys – and it is usually boys.” He adds: “There is a gender expectation that women are held to higher standards around ethical behaviour. It’s hard to imagine a female Boris Johnson or Aaron Banks.”

Canadian psychology professor Jordan Peterson has pointed to women having a “high level of agreeableness, to be cooperative and compassionate”. Would this make women better leaders than men on the whole, yet paradoxically lead them to rule themselves out of or be overlooked for top roles?

Briner suggests this is the case for women and men: “We say we want good people as leaders but it may be that good people don’t want to be leaders.” He says that people fear they will be asked to be dishonest and implement things they don’t agree with, “but paradoxically these are the people with the sense of responsibility who might be best.”

For Kate Cooper, women are more risk averse than men and work harder at relationships. Their ability to empathise is also greater. “This means they are more likely to be guided by ethical principles,” she says. “Studies show that women work more collaboratively and fixate less on the task.”

We say we want good people as leaders but it may be that good people don’t want to be leaders” – Rob Briner

Elva Ainsworth supports this view: “Women tend to be more conscientious and rule-following so supporting and empowering them as leaders will also help.”

But Duff warns against stereotyping: “If you ask men and women the question about which gender takes a more ethical to decision-making, intuitively, both men and women will opt for women. This, however, may simply reflect the wider stereotypical qualities that we assign to male leaders (pushy, assertive, risk-oriented, task-focused) and female leaders (nurturing, considerate, emotionally intelligent). But these are social stereotypes, rather than facts that are grounded in reality. They perpetuate the view that female leaders are inherently different to male leaders, when in fact, it is the lens through which they are viewed that is different.”

Ballot box dangers

Perhaps the ballot box gives us an opportunity to feed that part of our nature that is irrational and unethical. There is no HR department to intervene and moderate our preferences. And, as Cooper says, the distance between us and those we vote for means we care less about individual characteristics.

But there could be a terrible risk in this. Ethical values in organisations can be weakened as chaotic leaders from the political sphere begin to interact with and exert influence over businesses.

JAB Holdings is a business based in Germany that now rivals Starbucks and Nestlé, owning chains including Pret A Manger, Krispy Kreme and Dr Pepper Snapple. Like many longstanding German companies, its history as a business that colluded with the Nazis and used forced labour under horrific conditions has become more widely known as it has expanded globally.

Its current chairman, Peter Harf, has urged the company to open up its archives so the truth about its past can come out. He told the New York Times recently that not enough voices in business were speaking up against what he felt was the re-emergence of nationalism and populism in Europe and the US. He said he lives in three places, London, New York and Milan where nationalism was on the rise and, as a result, no longer considers shareholder capitalism to be value neutral. In the age of Trump, Brexit and Salvini, he said, “businesses can no longer pretend that they are operating in a value-free space. Everybody needs to take a stance. I’m very scared of what’s happening.”

Sign up to our weekly round-up of HR news and guidance

Receive the Personnel Today Direct e-newsletter every Wednesday

Every time business leaders make decisions, he said, they should ask: “What does this mean for our children, our future? In history, businesses have enabled populists… it is vital we do whatever we can to bring tolerance and equality to the communities where we live” and actions such as those of JAB’s owners in the thirties “are a part of history that is never repeated.”

2 comments

All leadership is both ethical and moral. Populism, Progressive-ism, Socialism, Islam-ism — all socio-economic philosophies — are guided by their particular brand of ethics and morality. So, what exactly do you mean by posing the question, “Is ethical leadership under threat from populism?” As most HR people are some combination of atheist, agnostic, Progressive and/or socialist, may we assume that you are asking if Populism is a threat the ethics of HR, whatever that might mean?

The article explains what is meant by ethical leadership and how it benefits companies… especially in an era where transparency is so highly valued and measured and rules are in place to avoid financial disasters. Reputation is a key factor too, and diversity. I don’t agree with the idea that ‘all leadership is ethical’. That is clearly untrue. The feature touches on the psychological aspects of leadership – what are known as the ‘dark triad’ of characteristics, which undermine leadership. Whatever your preconceptions about HR (atheism is fairly widespread beyond HR departments!) I would argue populism, which so often involves trying to whip people up on spurious grounds, is a threat to sound decision-making in businesses and government.

Comments are closed.